Dual Fabric Architecture for Virtualized Industrial Applications

Available Languages

Bias-Free Language

The documentation set for this product strives to use bias-free language. For the purposes of this documentation set, bias-free is defined as language that does not imply discrimination based on age, disability, gender, racial identity, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality. Exceptions may be present in the documentation due to language that is hardcoded in the user interfaces of the product software, language used based on RFP documentation, or language that is used by a referenced third-party product. Learn more about how Cisco is using Inclusive Language.

- US/Canada 800-553-2447

- Worldwide Support Phone Numbers

- All Tools

Feedback

Feedback

vPLCs and the shift in control boundaries

Solution Benefits of the Dual Fabric SD-Access Architecture

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

Industrial Ethernet Communication Characteristics

Traffic Model for Manufacturing Applications

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture Overview

Why Dual Fabric Starts with SD-Access

Creating Dual SD-Access Fabrics for Critical Applications

Architecture Takeaways for vPLC Workloads

PRP Fundamentals and Terminology

Solution Architecture Components

Validated Hardware and Software

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture Networking Design

Management and Policy Plane Considerations

Real-Time Traffic Connectivity to Dual Fabrics

Non-Real-Time Traffic Handling

Time Distribution Connectivity for Safety PLCs

Summary of Architectural Characteristics

PRP Operation Across Dual SD-Access Fabrics

PRP RedBox Placement in the Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

Layer 2 and Layer 3 Boundaries in Dual SD-Access Fabric

Example: Layer 2 and Layer 3 Boundaries for PRP and Non-PRP VLANs

PRP Supervisory Frames and Default Behavior

Implications in SD-Access Based Fabrics

PRP supervision VLAN aware mode for Scalable Deployments

Example: PRP Scale on Centralized Data Center for vPLC

Operational Guidance for PRP supervision VLAN aware mode Configuration

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic Priority Model

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic at the Industrial Access Layer

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic and VXLAN Encapsulation

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic Handling Inside the SD-Access Fabric

Restoring Layer 2 Priority for Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic at Fabric Egress

Summary: End-to-End PROFINET Frame Handling

(1) Industrial Access – Native PROFINET Frame

(2) SD-Access Fabric Ingress – Classification and VXLAN Encapsulation

(3) Transit Across the SD-Access Fabric – Routed Transport with Preserved Priority

(4) SD-Access Fabric Egress – Decapsulation and Priority Preservation

(5) Virtual Switch to vPLC – Layer 2 Delivery

Consistency Across Both Fabrics

Key QoS Design Principles for Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

Layer 2 Flooding and Multicast Requirements

Catalyst IE3400 Commissioning and Replacement Procedures

Operational Considerations for PEN/RedBoxes

Placement of Industrial Ethernet Switches in SD-Access Based Manufacturing Networks

Design Considerations and Operational Constraints

IP Directed Broadcast for Silent Host Use Cases

IT and OT Collaboration and Shared Infrastructure Considerations

Collaboration and Operational Alignment

Shared vs. Separated Infrastructure

Silent Hosts in OT Environments

NAT Below the Fabric Edge: OT-Specific Considerations

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture Security Design

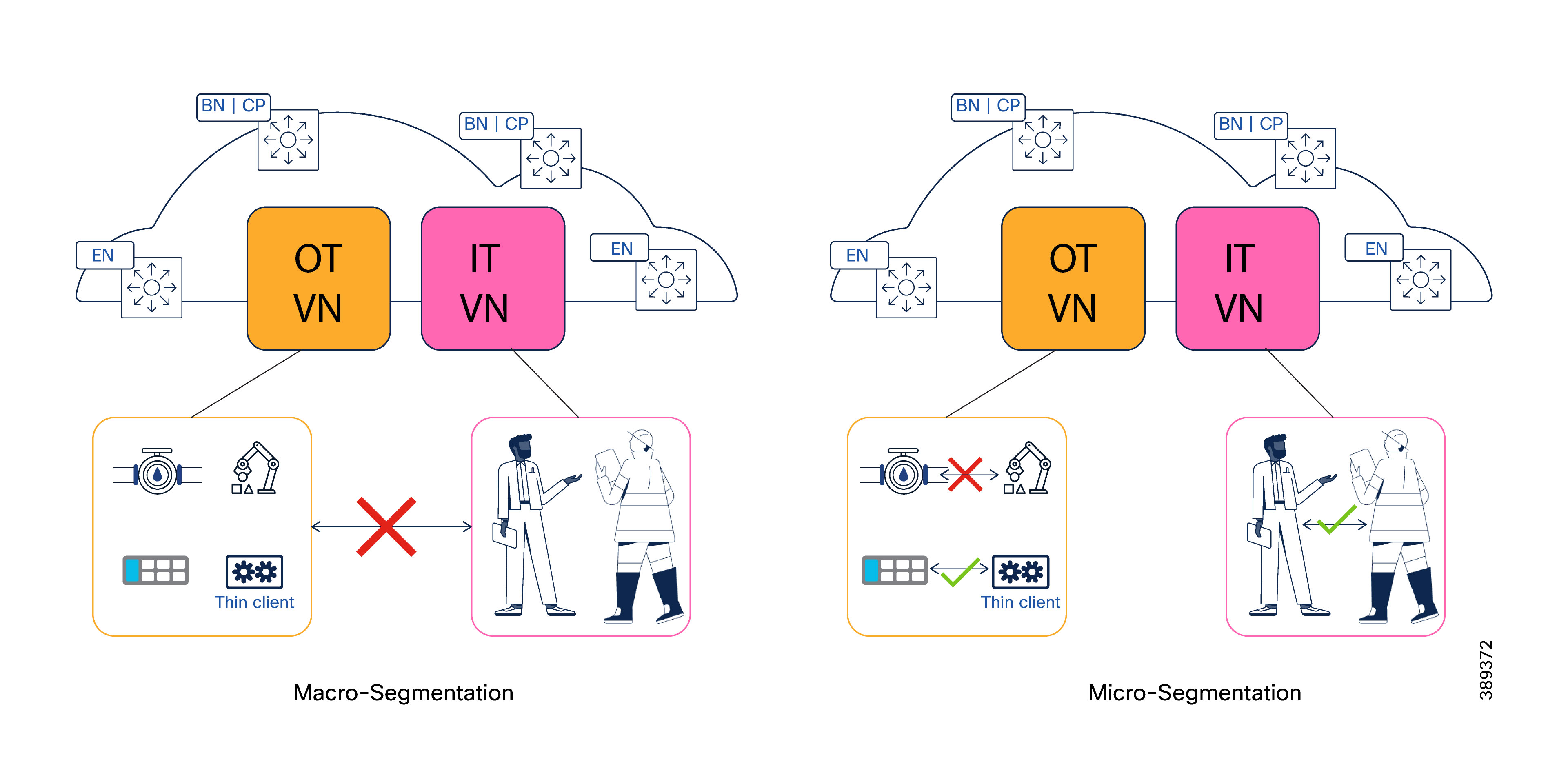

Macro-segmentation for OT Security

Micro-segmentation for Manufacturing Networks

How OT Segmentation Differs from Campus Networks

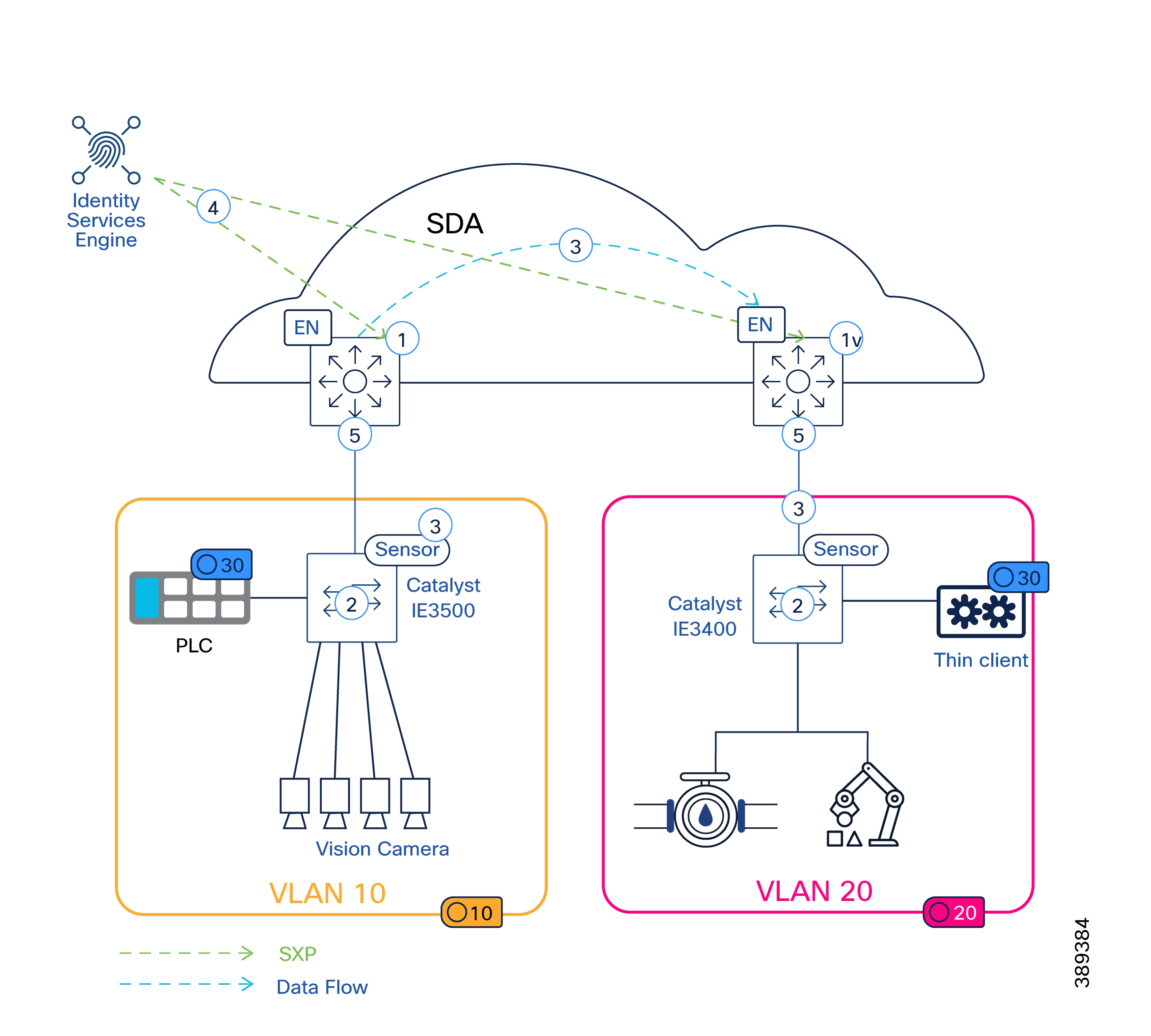

TrustSec Segmentation Design Principles for OT Networks

TrustSec Classification in OT Environments

TrustSec Propagation Across SD-Access and Non-Fabric Domains

TrustSec Enforcement Models in OT Designs

Scale and Platform Considerations

Default-Deny Policy Considerations in SD-Access Based Manufacturing Networks

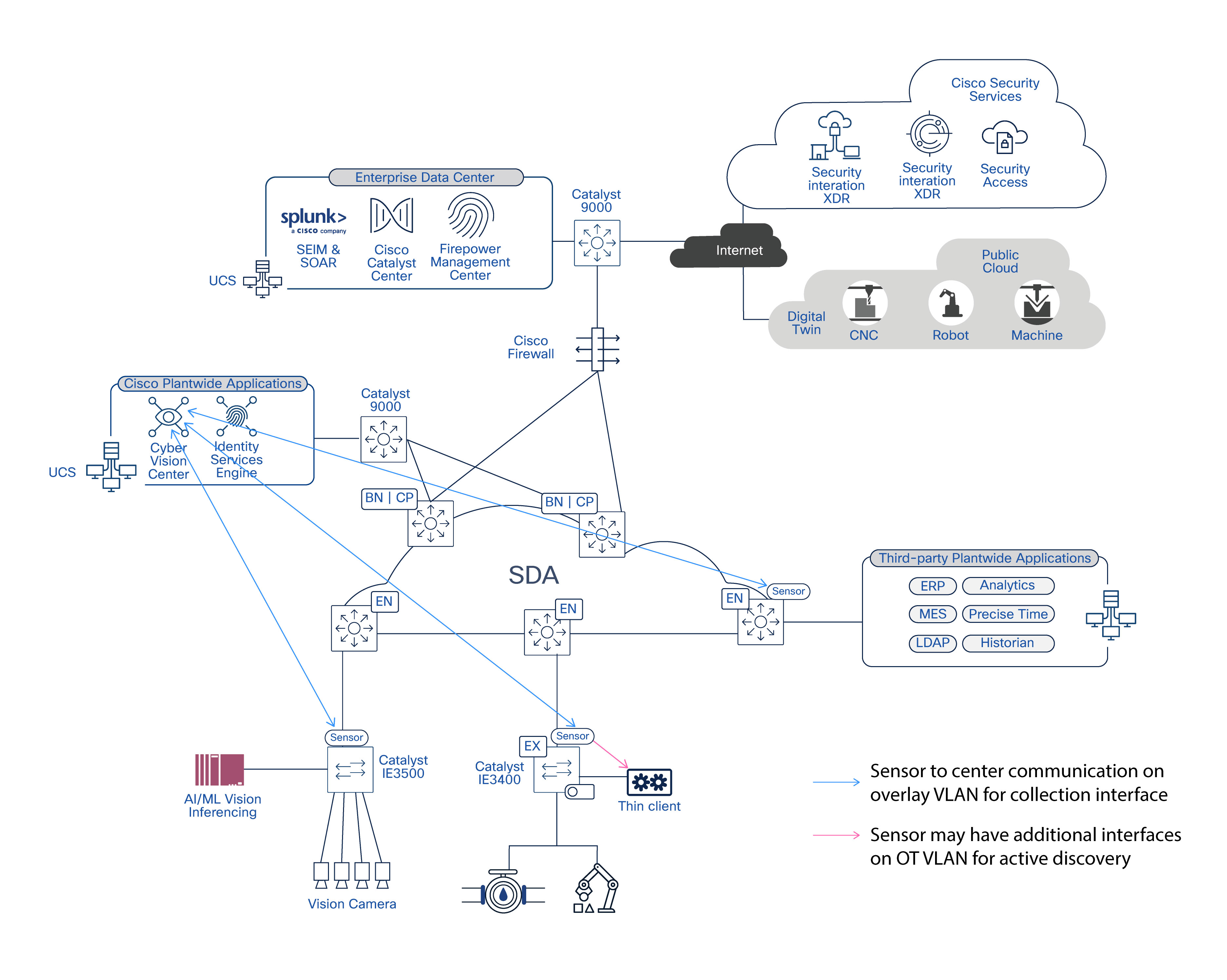

Cyber Vision for OT Visibility in SD-Access Based Manufacturing Networks

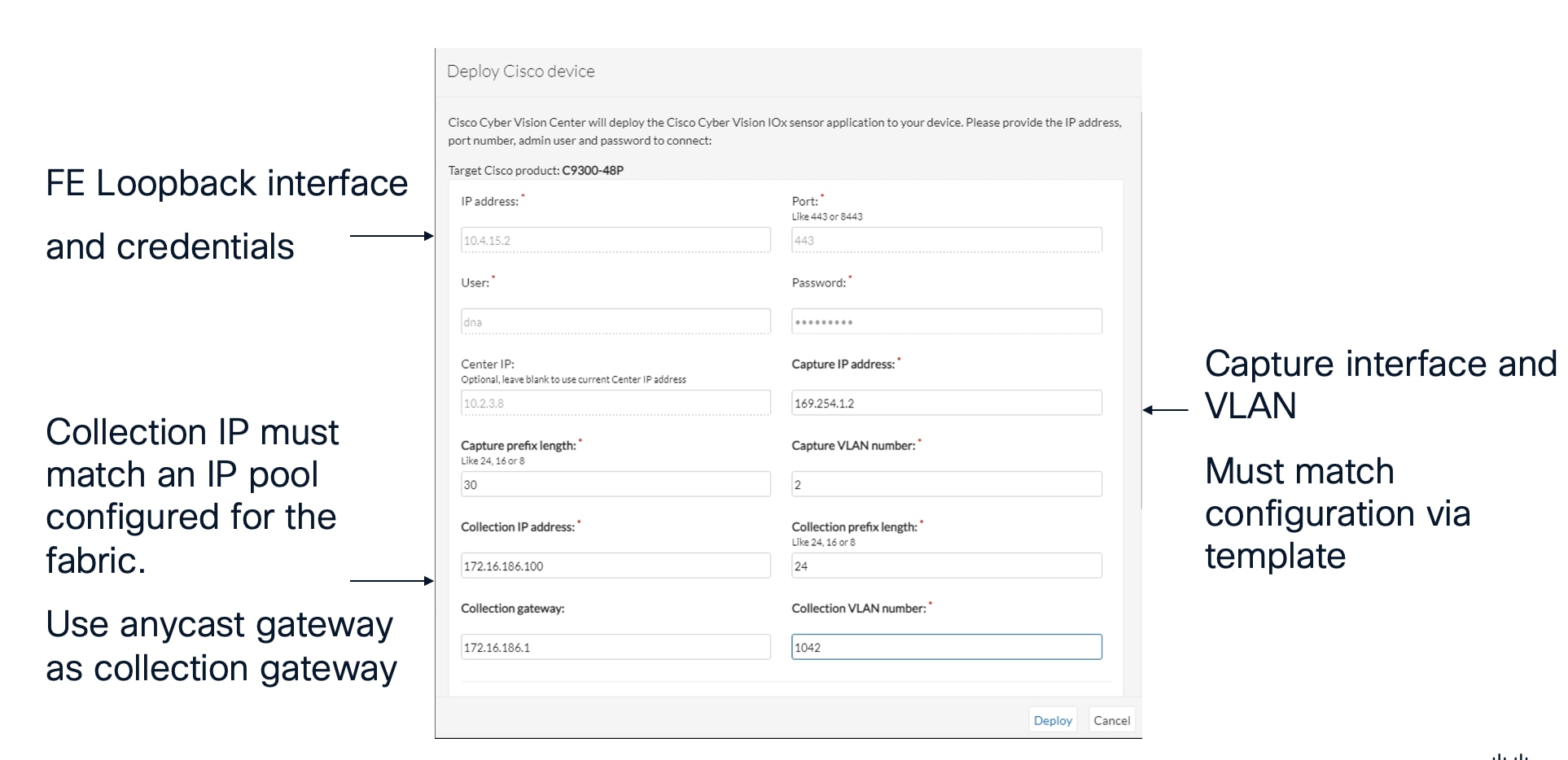

Cyber Vision Deployment in SD-Access Architecture

SD-Access Specific Considerations for Cyber Vision Integration

Secure Equipment Access (SEA) in SD-Access Based Manufacturing Networks

Integration of SEA with Cisco Cyber Vision

SEA Deployment in SD-Access Architecture

Bandwidth, Replication, and Platform Sizing

Failure and Recovery Scenarios

Management Plane Sizing, Latency, and Operational Scale

Layer 2 Flooding and Underlay Multicast Scale

vPLC and Data Center / Virtualization Integration

Control Plane and Border Node Scale

Design Recommendations Summary

Validation Summary and Results

Validation Scope and Objectives

Traffic and Congestion Validation

Failure and Recovery Validation

Latency and Jitter Measurements

Executive Summary

As an initial step towards software-defined automation, manufacturing environments are increasingly adopting virtualization architectures to improve scalability, lifecycle management, and integration with advanced analytics and AI-driven applications. They are virtualizing a range of compute focused devices and applications including engineering workstations, human-machine interfaces (HMIs) and even the brains of the industrial automation systems, the programmable logic controller (PLC). While virtualization delivers clear benefits, it also fundamentally alters the assumptions under which traditional PLC networks were designed. Control workloads that were once tightly coupled to a local backplane or a single access switch now depend on a shared, distributed Ethernet infrastructure and take advantage of running on more capable server systems.

This Cisco Validated Design (CVD) provides architectural guidance for deploying dual independent Ethernet fabrics to support virtualization, and especially vPLC workloads in manufacturing environments. The design focuses on preserving bounded latency and jitter, fault isolation, and operational behavior, while integrating critical capabilities such as control traffic prioritization with Quality of Service (QoS), hitless network resiliency with the Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP), industrial cybersecurity with Cisco Cyber Vision for visibility, remote access with Secure Equipment Access (SEA), and Cisco TrustSec-based segmentation.

vPLCs and the shift in control boundaries

Benefits and Challenges of vPLC Workloads

Virtualizing PLC workloads introduces architectural and operational benefits that extend beyond compute consolidation. When properly designed, vPLC architectures enable greater flexibility, resilience, and lifecycle control while preserving the time-sensitive behavior required by manufacturing applications.

Key Benefits

● Workload Mobility and Flexibility

vPLCs are no longer tied to a specific physical controller or cabinet location. Control workloads can be placed, relocated, or recovered based on operational needs without rewiring field devices or rearchitecting the network.

● Improved Availability and Recovery

Virtualization enables faster recovery from hardware failures through Virtual Machine (VM) restart, migration, or redeployment. This reduces mean time to recovery (MTTR) compared to replacing or reconfiguring physical PLC hardware.

● Simplified Lifecycle Management

Software-based PLCs simplify firmware updates, backups, version control, and rollback. Control logic can be managed using standardized IT workflows while maintaining OT change-control practices.

● Improved Security

Ability to quickly upgrade the software with security updates reducing risks to the application

● Scalability and Resource Efficiency

Compute resources can be shared across multiple control workloads, allowing capacity to be scaled incrementally as production requirements evolve, without overprovisioning dedicated hardware.

● Foundation for Advanced Use Cases

vPLC architectures facilitate closer integration with analytics, AI inference, digital twins, and simulation environments by collocating control workloads with compute and data resources.

● Capital cost savings

By using scalable data center quality server platforms, manufacturers save significant capital expenditures from the ruggedized and limited PLC hardware.

Key Challenges

Traditional PLC architectures rely on implicit assumptions:

● Fixed physical location

● Connected directly to the local network of the industrial devices it’s controlling

● Predictable, minimal network hops

● Limited exposure to shared infrastructure

Virtualization breaks these assumptions. When PLC software is deployed on virtual machines, control logic execution becomes dependent on the behavior of the underlying compute, storage, and network infrastructure. Latency, jitter, congestion, and fault domains that were previously irrelevant now directly influence control system stability.

Solution Benefits of the Dual Fabric SD-Access Architecture

This Cisco Validated Design (CVD) addresses the key challenges of virtual Programmable Logic Controller (vPLC) deployments in manufacturing. It combines dual independent Software-Defined Access (SD-Access) fabrics with industrial-grade redundancy, prioritization, and visibility mechanisms.

Key Technical Features

● Flexible Layer 2 Connectivity

SD-Access uses Virtual Extensible LAN (VXLAN) overlays over a routed Layer 3 network to provide logical Layer 2 adjacency, enabling industrial applications to operate within the same subnet when needed

● Predictable Control Traffic Behavior During Failures

Dual SD-Access fabrics combined with selective PRP eliminate reliance on fabric convergence for time-sensitive control traffic, allowing critical applications to continue operating during link or node failures.

● Strong Fault Isolation

Each fabric operates independently with its own control and forwarding planes, limiting the impact of failures, misconfigurations, or maintenance activities.

● Selective Redundancy Based on Application Needs

PRP is applied only to traffic that requires it, protecting critical flows while avoiding unnecessary bandwidth duplication.

● Consistent End-to-End Traffic Prioritization

Traffic classification and queuing are aligned across industrial access, SD-Access fabrics, and the data center, ensuring uniform treatment of control traffic regardless of location.

● Scalable Visibility Without Additional Infrastructure

Embedded Cyber Vision sensors provide OT visibility across both fabrics without SPAN, additional appliances, or shared forwarding dependencies.

● Strong segmentation (micro and macro) with easy to deploy TrustSec Scalable Group Tags (SGTs) and Virtual Routing Frameworks (VRFs).

Together, these benefits provide a resilient and operationally practical foundation for deploying vPLC workloads in modern manufacturing environments.

Intended Audience

The CVD is intended for manufacturing network architects, OT and IT collaboration teams, and system integrators designing production networks where control availability and predictability directly impact safety, quality, and uptime. The guidance reflects real-world factory constraints, combined OT/IT operational models, and the practical challenges of connecting industrial ethernet networks to enterprise and data center infrastructures.

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

Industrial Ethernet Communication Characteristics

Many of the requirements driving the dual fabric architecture originate from the behavior of industrial Ethernet protocols used in manufacturing environments. This CVD focuses on PROFINET, as it is the supported protocol for the validated vPLCs.

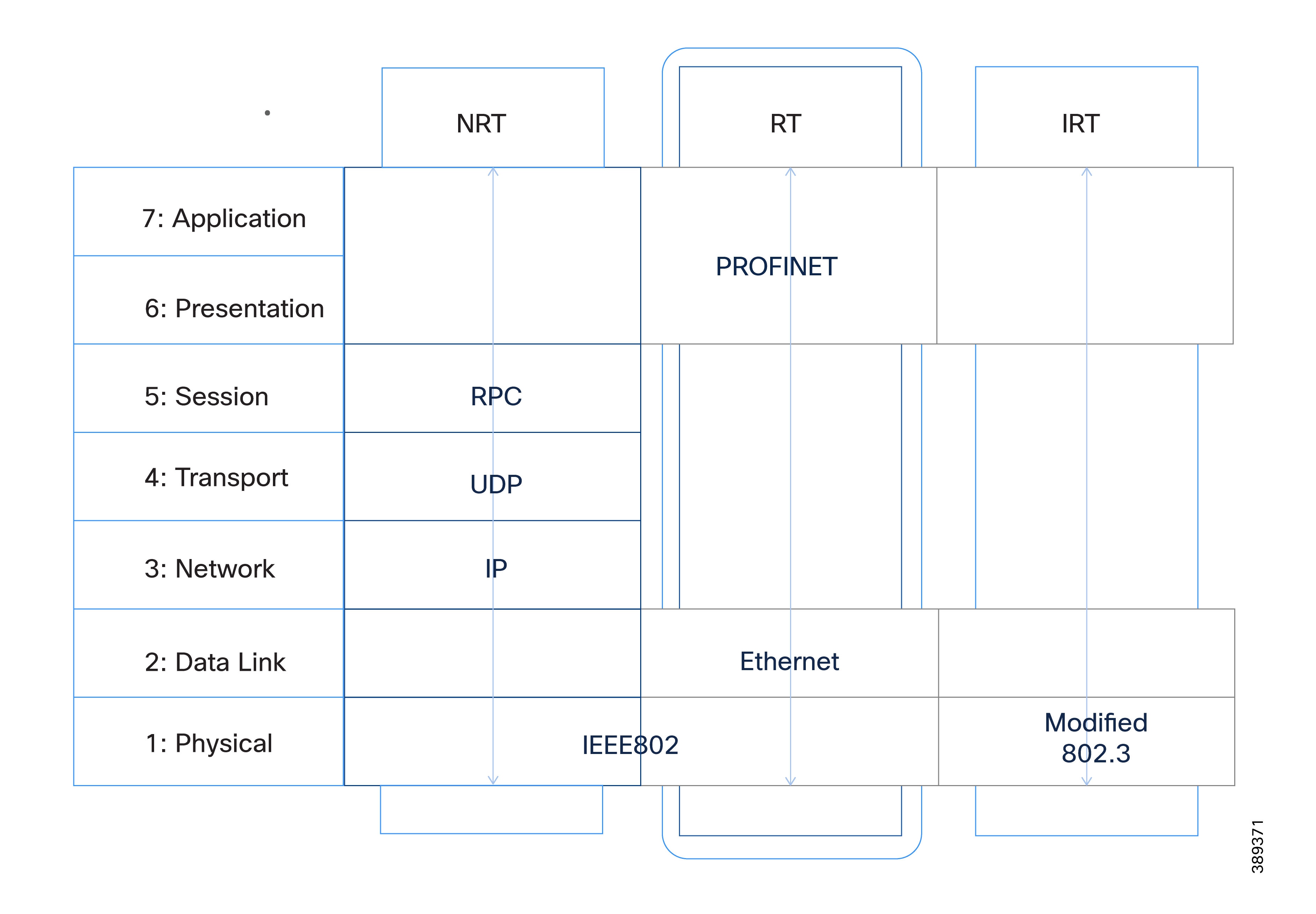

PROFINET RT (Real Time), along with other industrial Ethernet protocols, operates directly at Layer 2 of the OSI model, using Ethernet frames identified by a specific EtherType and without a Layer 3 (IP) header. Because this traffic cannot be routed, controllers and field devices must reside within the same Layer 2 domain.

In addition to cyclic real-time traffic, PROFINET relies on non-real-time (NRT) communication for functions such as diagnostics, commissioning, and configuration.

The diagram illustrates how PROFINET uses different communication channels — RT, NRT — aligned with the OSI protocol stack to support real-time control, general traffic, and high-performance deterministic communication. IRT (Isochronous Real Time) is included for reference only. This document focuses on PROFINET RT and NRT, which operate over standard Ethernet. PROFINET IRT requires specialized hardware and is therefore outside the scope of this design. Source: PROFINET University, PROFINET Communication Channels.

Additionally, PROFINET DCP (Discovery and Configuration Protocol) uses multicast Layer 2 frames to identify and assign device parameters during startup and maintenance operations.

These characteristics impose several constraints on the network:

● Layer 2 adjacency must be preserved between controllers and field devices

● Multicast traffic must be supported for discovery and commissioning workflows

● Short communication interruptions during network reconvergence may not be tolerated by real-time traffic

Traditional enterprise and data center networks are designed around Layer 3 boundaries, routing segmentation, and IP subnet isolation, and do not natively support extending Layer 2 domains across large physical areas or between factory floors and centralized compute environments.

These protocol characteristics are a key driver for the architectural choices described in this CVD.

Traffic Model for Manufacturing Applications

Modern manufacturing networks support a diverse set of applications with very different performance, availability, and fault-tolerance requirements. Virtualized PLCs are one of these applications, but they coexist with HMIs, supervisory systems, data integration platforms, analytics pipelines, and edge and cloud services.

Unlike traditional enterprise applications, many manufacturing workloads are sensitive not only to packet loss, but also to latency, jitter, and packet reordering. Some applications require bounded latency and jitter behavior under all conditions, while others prioritize scalability or data throughput.

As a result, the dual fabric architecture must be designed around application requirements, in addition to devices or bandwidth utilization.

This section defines the primary traffic classes commonly observed in manufacturing environments that include vPLC workloads. The traffic classes described here are representative, not exhaustive, and are intended to provide a structured framework that can be extended while preserving determinism, fault isolation, and operational clarity.

Traffic Classes

The following traffic classes typically appear in manufacturing networks supporting virtualized control and application workloads:

Table 1. Manufacturing Traffic Classes and Design Priorities

| Traffic Class |

Purpose |

Key Characteristics |

Priority |

| Real-Time Control Traffic |

Closed-loop control between control applications (e.g., vPLCs) and field devices or distributed I/O. |

Deterministic, cyclic, extremely sensitive to latency and jitter; tolerates zero packet loss. |

Highest |

| Non-Cyclic Control and Event Traffic |

Acyclic control exchanges, diagnostics, alarms, and state changes. |

Time-sensitive and bursty; more tolerant than real-time control. |

High |

| Redundant Application Traffic (PRP) |

Application traffic duplicated across both fabrics using the Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP). |

Involves frame duplication and sequence handling at endpoints or Redundancy Boxes (RedBoxes); increases bandwidth consumption. |

Inherits protected traffic priority |

| Engineering and Maintenance Traffic |

Engineering stations, configuration tools, firmware updates, and commissioning activities. |

Bursty and non-deterministic; operationally important but not time-critical. |

Medium |

| Supervisory and HMI Traffic |

Operator commands, HMI updates, visualization, and status polling. |

Latency-sensitive but tolerant of brief delays; often involves high east–west volume. |

Medium |

| Application and Integration Traffic |

Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES), analytics, and edge processing using Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC UA), Representational State Transfer (REST) APIs, and similar protocols. |

Throughput-oriented; tolerant of higher latency and occasional packet loss. |

Low |

| Monitoring and Visibility Traffic |

Asset discovery, telemetry, and Cisco Cyber Vision metadata. |

Passive and non-intrusive; does not impact forwarding behavior. |

Low |

| Management and Orchestration Traffic |

Virtualization management, Cisco Catalyst Center operations, logging, and lifecycle management. |

IT-owned and non-deterministic; explicitly deprioritized. |

Lowest |

Design Goals

The dual fabric architecture defined in this CVD is driven by the following goals:

● Preserve low latency and jitter for cyclic I/O behavior under normal and failure conditions

● Eliminate single points of failure in the network path for critical applications

● Maintain predictable, bounded failover behavior

● Enable security and visibility without impacting control traffic

● Enable structured OT/IT collaboration

Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture Overview

The following sections provide an overview of the Dual SD-Access Fabric architecture and the design principles that underpin it. It introduces the use of two independent SD-Access fabrics to achieve fault isolation and deterministic behavior for industrial workloads, and sets the context for why SD-Access is the logical foundation for a dual-fabric manufacturing network.

Why Dual Fabric Starts with SD-Access

The dual-fabric architecture described in this CVD is based on two fully independent SD-Access fabrics. These fabrics operate as two separate networks, not as redundant components within a single fabric.

SD-Access uses VXLAN encapsulation to decouple Layer-2 connectivity from physical topology. This capability fundamentally changes how industrial networks can be designed and operated, especially when supporting virtualized workloads such as vPLCs.

In traditional manufacturing networks, physical topology dictates logical design. If two devices, for example a PLC and an I/O device, must reside in the same subnet, they must also be physically connected within the same VLAN domain. Extending that VLAN across the plant floor often results in a large flat network, a complex spanning-tree design, and tightly coupled failure domains.

SD-Access removes this constrain by introducing VXLAN. With VXLA, Layer-2 connectivity is extended over a routed network, making devices appear physically close even when they are deployed in different locations across the plant. Logical adjacency is preserved without requiring a contiguous Layer-2 domain across the factory floor.

In practical terms, this means:

● A PLC and its associated I/O devices can share the same subnet regardless of physical location

● VLAN membership becomes a logical construct rather than a wiring requirement

● Physical rewiring is no longer required when systems are redesigned or relocated

In essence, the application defines the connection requirement between devices, and the network facilitates that connection.

If a set of PLCs, I/O devices, and HMIs belong to same VLAN, they remain a coherent logical group even when distributed across different production areas. SD-Access provides this flexibility while maintaining segmentation and control, without creating large flat networks.

This capability forms the foundation for modern manufacturing architectures, enabling virtualization, workload mobility, and system redesign without continuous physical network changes. However, this flexibility alone does not eliminate the effects of convergence.

Creating Dual SD-Access Fabrics for Critical Applications

Dual fabric refers to the deployment of two completely independent SD-Access fabrics, each operating as a standalone network.

There are no shared links, no shared control protocols, and no shared forwarding state between the two fabrics. From a network perspective, Fabric A and Fabric B behave as two separate networks.

A single SD-Access fabric already provides resiliency through ECMP and fast convergence, but it still represents one convergence domain. When a link or node failure occurs, traffic using the affected path experiences a brief interruption while the fabric reconverges. For many applications, this behavior is acceptable. For certain industrial workloads, it is not.

To overcome this, the architecture introduces traffic duplication across two independent SD-Access fabrics, ensuring that a failure or convergence event in one fabric has no impact on traffic carried by the other.

Each SD-Access fabric includes:

● Its own physical switching infrastructure

● Its own control plane (IS-IS, LISP)

● Its own forwarding plane (VXLAN)

● Its own failure domain

● Shared Management plane in Cisco Catalyst Center

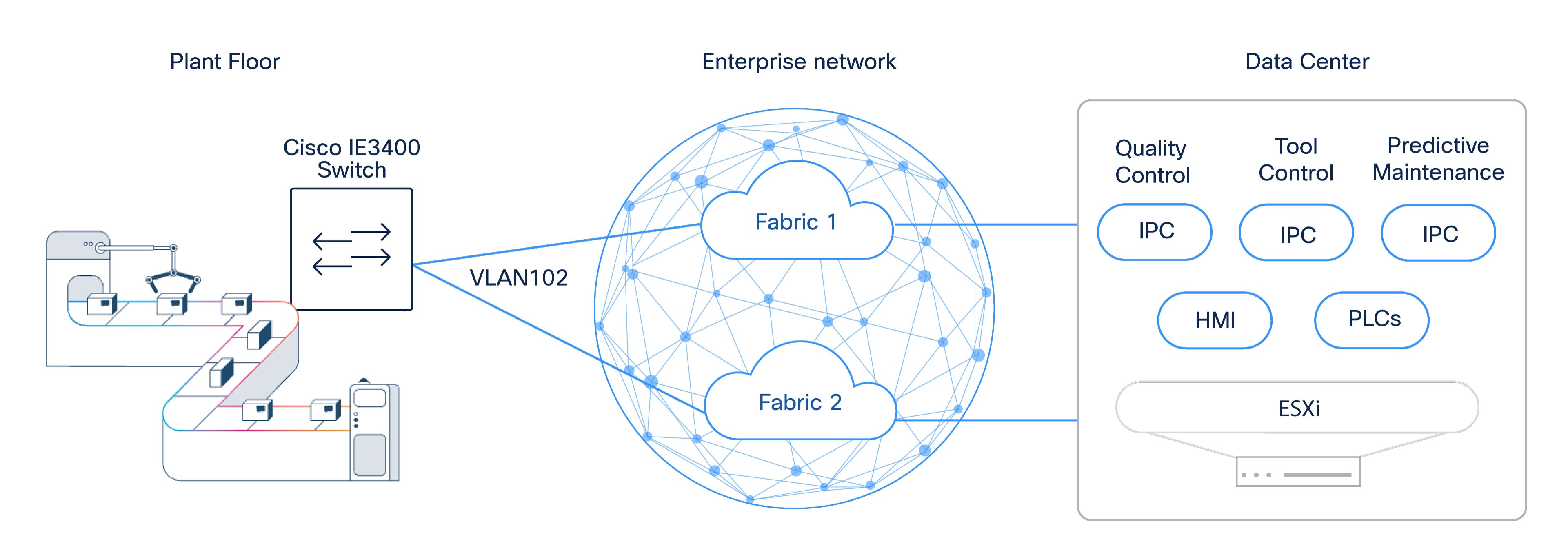

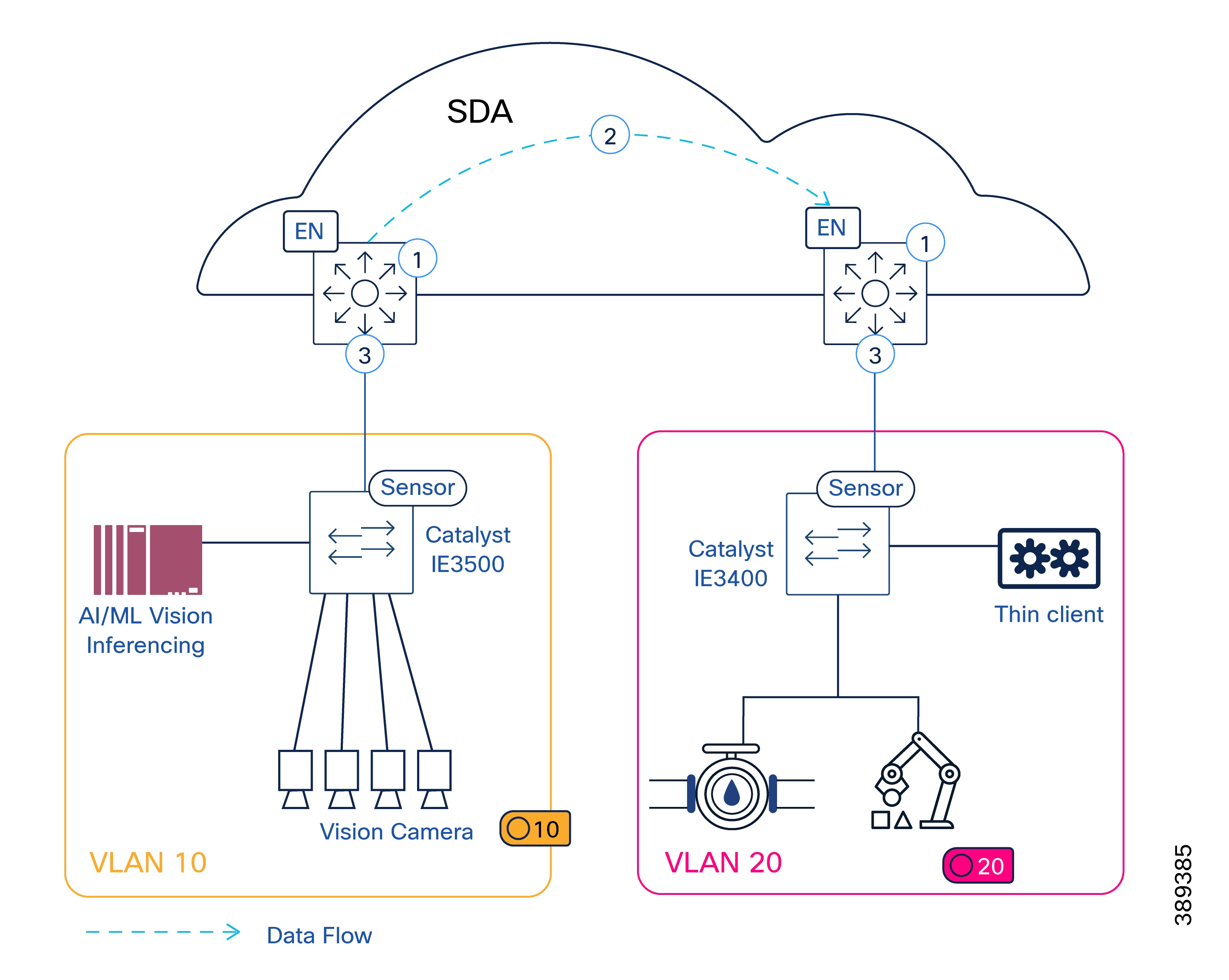

As illustrated in the diagram, the architecture is composed of two independent SD-Access fabrics, each operating as an isolated fault domain to prevent failures or convergence events in one fabric from affecting the other.

Equal, Active Fabrics

In a Dual SD-Access Fabric architecture, both fabrics operate simultaneously and independently, providing parallel active paths for application traffic. While some applications require uninterrupted communication, using both fabrics introduces additional operational complexity and overhead. For this reason, traffic should use both fabrics only when application requirements demand zero tolerance to packet loss or interruption. Traffic duplication is therefore driven by each application’s tolerance to loss, interruption, and recovery time.

Traffic duplication therefore needs to be driven by application tolerance to loss and interruption:

● Applications that can tolerate brief interruption may use only one fabric.

● Applications that cannot tolerate packet loss or interruption should leverage both fabrics simultaneously, transmitting traffic in parallel across both the fabrics.

Each traffic class must be evaluated to determine whether the application requires near zero-loss resiliency or can tolerate brief service disruptions. The table below provides a decision aid to guide traffic duplication across one or both SD-Access fabrics based on these requirements.

Table 2. Traffic Duplication Across Dual SD-Access Fabrics

| Application Requirement |

Typical Traffic |

Fabric Usage |

Notes |

| Tolerates brief interruption |

Engineering, diagnostics, non-critical monitoring. |

Use one fabric only |

Brief disruption is acceptable during failures or reconvergence. |

| Sensitive to interruption but tolerant to loss |

Human-Machine Interface (HMI), supervisory control. |

Use one fabric only |

Placement depends on operational risk and recovery expectations. |

| Near zero-tolerance to loss or interruption |

Real-time control, critical virtual Programmable Logic Controller (vPLC) I/O. |

Use both fabrics |

Required for continuous, uninterrupted communication. |

| Throughput-oriented, non-deterministic |

Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES), analytics, Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC UA). |

Use one fabric only |

Traffic is contained and rate-limited. |

Regardless of whether traffic is carried on one fabric or both, all traffic must be consistently classified, prioritized, and mapped to appropriate queues in each SD-Access fabric. Time-sensitive control traffic is isolated and prioritized, while non-deterministic and data-centric workloads are rate-limited and contained. This consistency is critical to ensuring predictable behavior across normal and failure conditions.

Further discussion of QoS mechanisms and policy design is provided later in this document.

The ability to use both fabrics simultaneously for selected traffic classes is enabled through the Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP). PRP allows frames to be transmitted over two independent networks at the same time, ensuring uninterrupted communication even in the presence of network failures.

PRP operation and design considerations are discussed later in this document.

Architecture Takeaways for vPLC Workloads

In this architecture:

● SD-Access provides Layer 2 extension over a routed fabric for flexible vPLC placement

● Dual fabrics with PRP provide the redundancy to ensure uninterrupted communication

Together, these elements allow modern SD-Access based dual-fabric deployments to support vPLC workloads requirements for strict availability and determinism.

PRP Fundamentals and Terminology

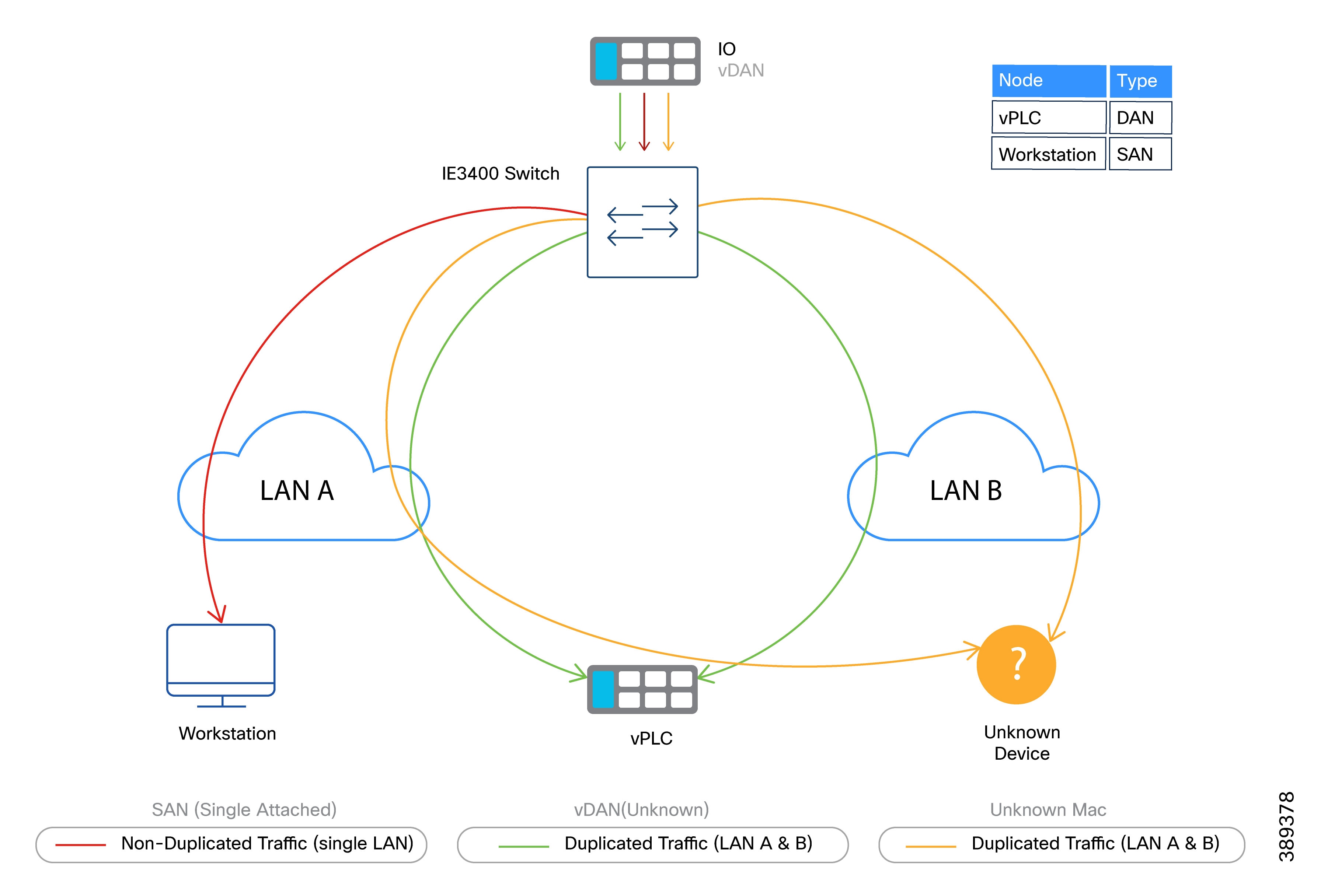

The Dual SD-Access Fabric architecture described in this CVD relies on duplication mechanism to provide uninterrupted communication for selected traffic classes. In particular, the design leverages the Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP). PRP is a Layer 2 redundancy mechanism defined in IEC 62439-3. PRP enables uninterrupted communication by transmitting duplicate Ethernet frames simultaneously over two independent networks.

PRP defines the following key components:

● DAN (Dual Attached Node)

An end device that is connected to two independent networks and transmits duplicate frames on both.

● SAN (Single Attached Node)

An end device that is connected to only one network and does not participate in PRP duplication.

● RedBox (Redundancy Box)

A device that enables an endpoint to participate in PRP by duplicating and terminating frames on their behalf.

● vDAN (Virtual DualAttached Node)

A logical PRP construct created by a RedBox on behalf of a single attached device. The RedBox presents the attached device to the network as if it were a DAN.

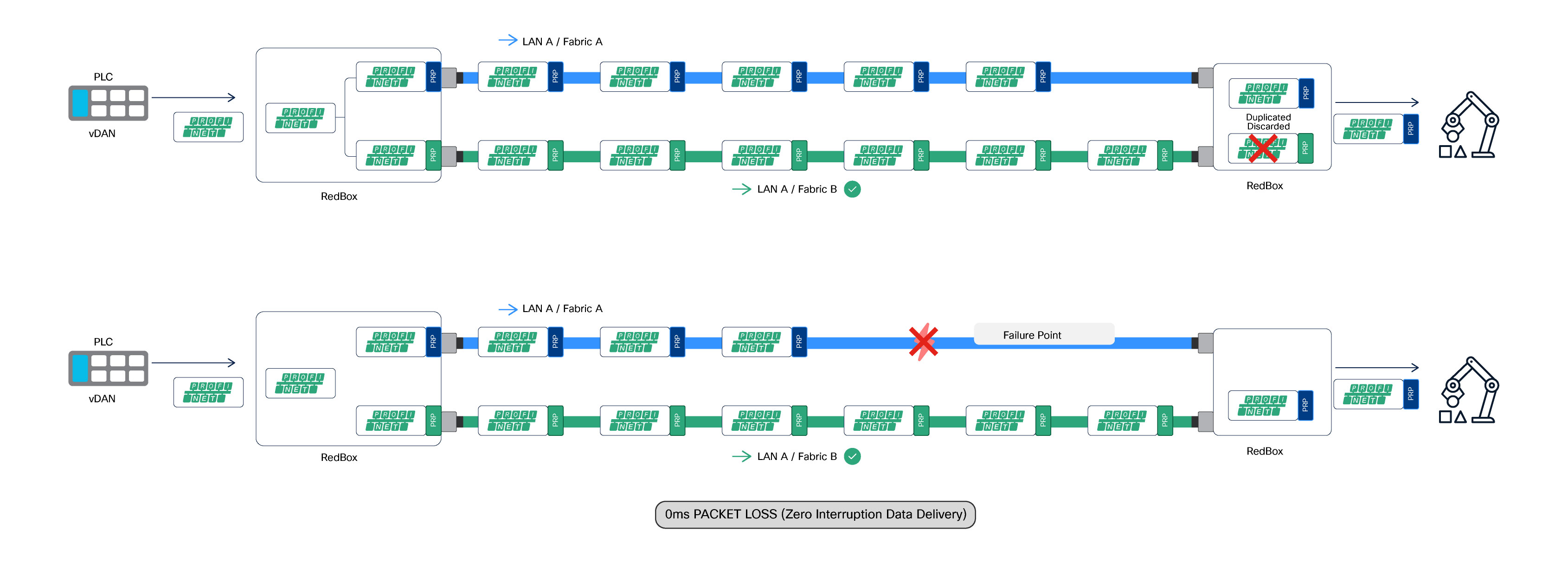

PRP operates entirely at the DANs or RedBoxes. Frames are duplicated and transmitted simultaneously over both independent networks, while the receiving endpoint accepts the first valid frame and discards the duplicate. The network infrastructure remains transparent to PRP operation. The figure below illustrates the concept.

As shown in figure below, frames are duplicated by the sending RedBox and transmitted simultaneously over both LAN A (Fabric A) and LAN B (Fabric B). Upon reception, the receiving RedBox accepts the first valid frame and discards the duplicate. In the event of a failure on one fabric, communication continues without packet loss or interruption, as PRP duplication and de-duplication are handled by RedBoxes at the network access layer and remain transparent to the SD-Access fabric infrastructure.

Solution Architecture Components

The architecture in this Cisco Validated Design (CVD) extends beyond the network layer. Delivering resilient and predictable virtual Programmable Logic Controller (vPLC) operations requires the coordinated design of multiple layers, each with distinct responsibilities.

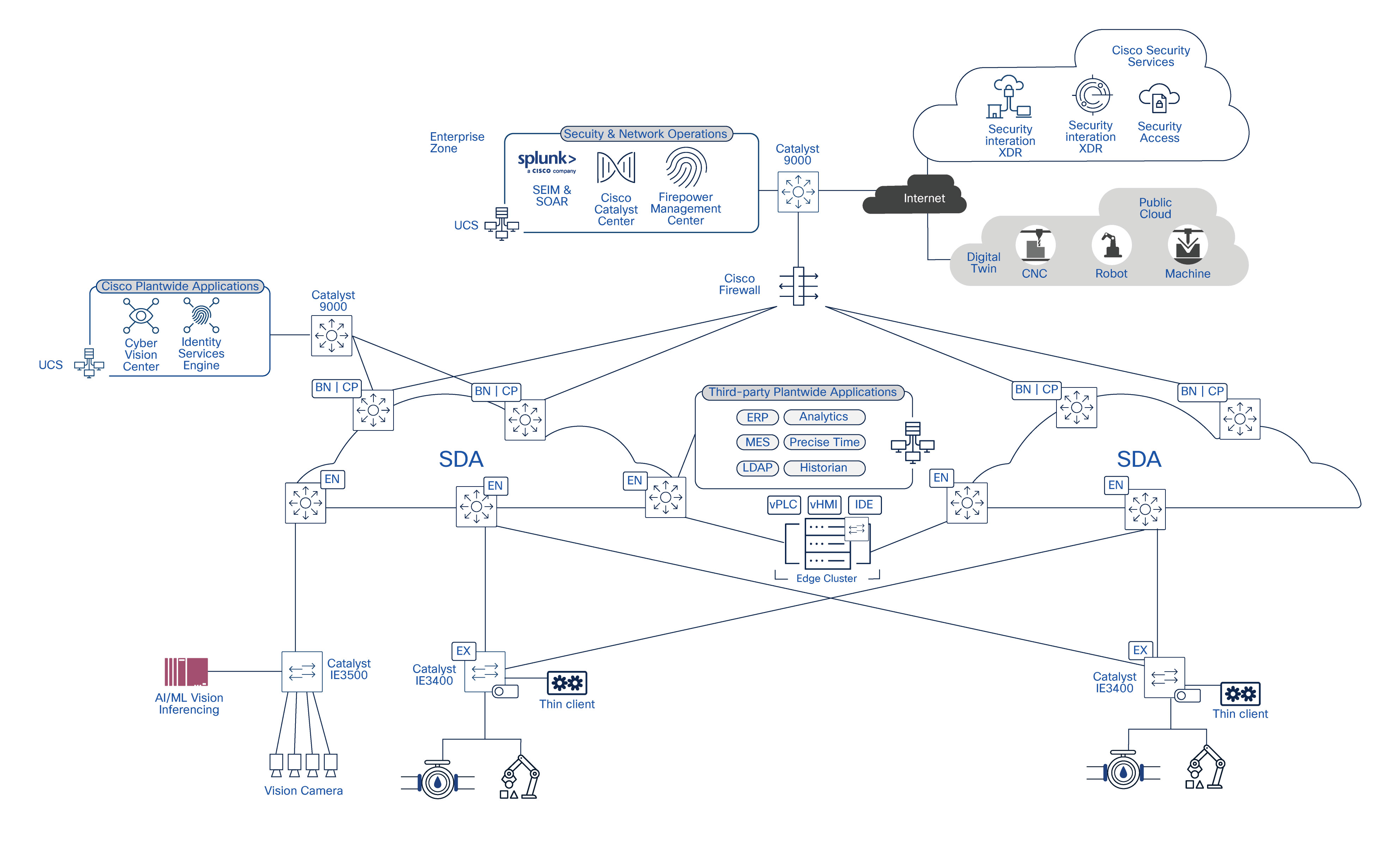

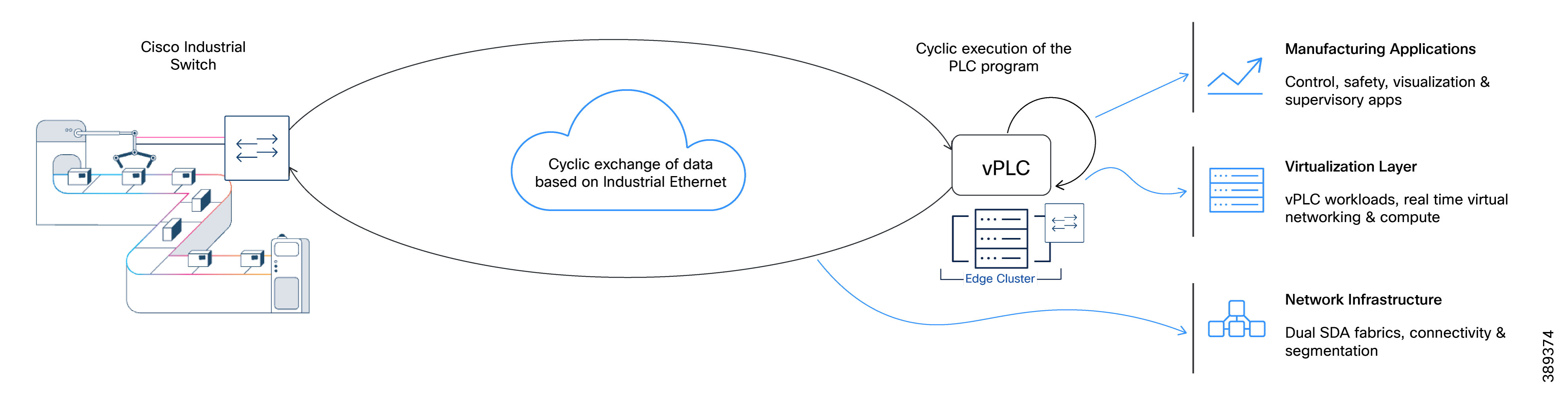

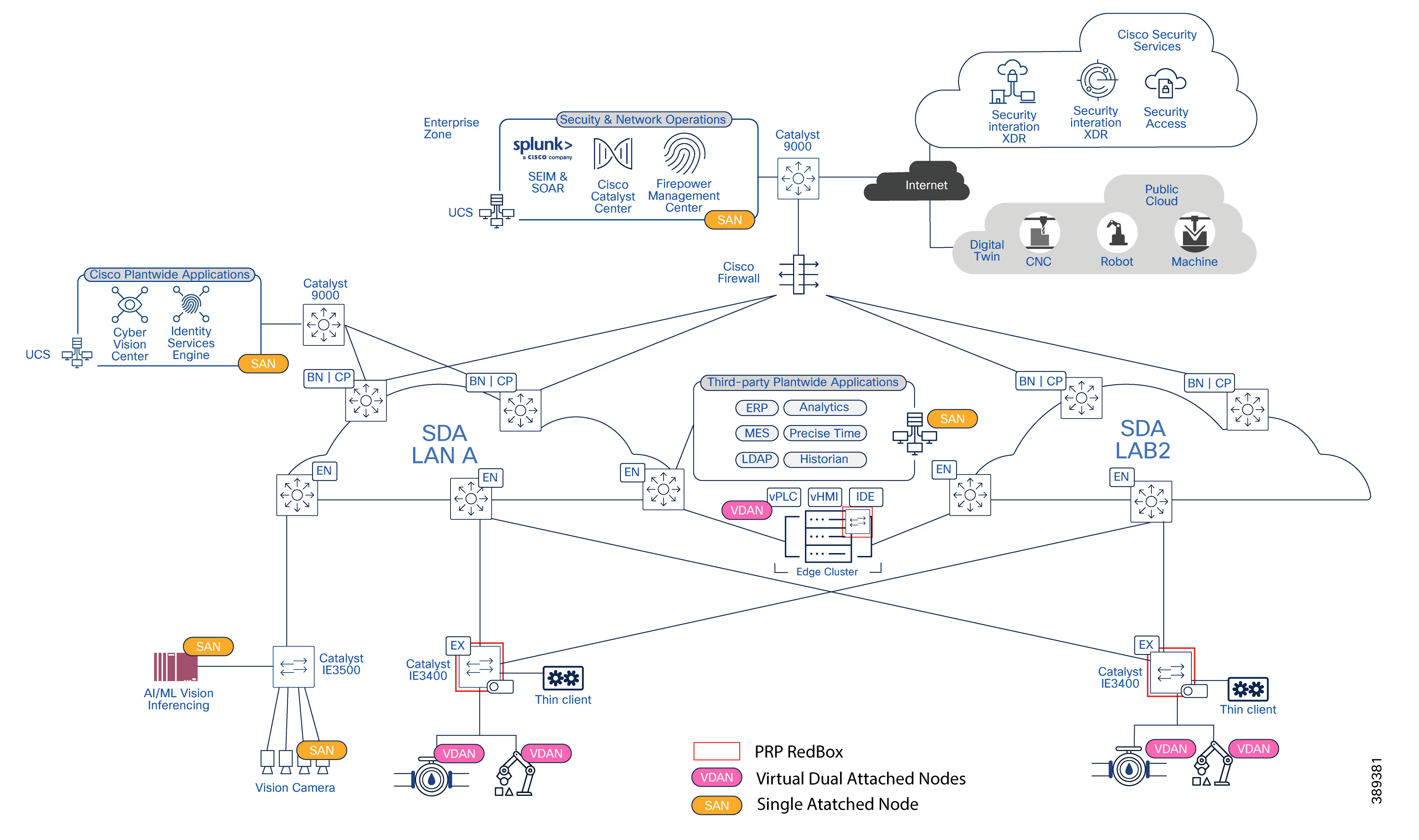

Figure 5 illustrates the major architectural components that support vPLC workloads. It highlights the interactions between manufacturing applications, the virtualization layer, and the underlying network infrastructure.

The solution comprises the following architectural components:

● Network Infrastructure: Dual Software-Defined Access (SD-Access) fabrics provide connectivity, segmentation, redundancy, and traffic prioritization from the cell/area zone to the data center.

● Virtualization Layer: The virtualization platform hosts virtual Programmable Logic Controller (vPLC) workloads. It provides the compute, virtual networking, and availability mechanisms that directly influence control application behavior. Unlike traditional enterprise workloads, vPLC performance and availability rely heavily on how the virtualization layer connects workloads to the underlying network.

● Manufacturing Applications: Control, safety, visualization, and supervisory applications impose specific latency, availability, and communication requirements on the underlying infrastructure.

This CVD focuses primarily on the network architecture while explicitly accounting for its interaction with the virtualization platform. The following sections briefly describe the virtualization platform and manufacturing applications before detailing the network architecture.

The Virtualization Layer

This CVD was validated using VMware Cloud Foundation (VCF), Broadcom’s integrated private cloud platform. Only the components that are architecturally relevant to the design described in this document are called out.

Components used in this CVD:

● ESXi (Hypervisor): hosts vPLC virtual machines and other manufacturing workloads.

● vCenter (Virtualization management): provides centralized management and lifecycle operations for the virtual environment. While operationally critical, vCenter is not involved in real-time traffic forwarding.

● NSX (Network and security virtualization): provides the virtual networking framework used to attach vPLC workloads to the factory network in a consistent and repeatable manner.

● Industrial Virtual Switch (IVS): a real-time virtual switch used to connect vPLC workloads to the OT network. IVS is designed to support industrial Ethernet communication patterns, predictable latency characteristics, and resilient connectivity for manufacturing applications. The virtual switch participates in maintaining application connectivity during network or infrastructure events without requiring changes to the control application itself.

● vSAN (Storage virtualization): provides shared, resilient storage for vPLC workloads. vSAN enables workload availability and restart without dependency on local disks, supporting infrastructure-level resiliency while maintaining predictable access to control application state.

Note: Refer to the vendor documentation for specific hardware and software requirements for the compute layer.

Manufacturing Applications in Virtualized Environments

This architecture supports various manufacturing applications increasingly deployed in virtualized environments. These applications impose strict requirements on availability, timing behavior, and operational continuity. You must consider these requirements alongside the underlying infrastructure design.

This section describes the primary application types validated in this CVD and their general operational characteristics. While vendor-specific implementations vary, the architectural requirements remain common across platforms.

Virtualized PLC (vPLC)

A virtualized PLC (vPLC) executes PLC control logic as software running on compute infrastructure, rather than on dedicated controller hardware. The control application executes inside a virtual machine or container and interacts with field devices over Ethernet-based industrial protocols.

Both Siemens and CODESYS provide virtual PLC implementations that are functionally equivalent to a physical PLC, while enabling centralized deployment, lifecycle management, and integration with IT infrastructure.

From an application perspective, vPLCs retain the same real-time communication requirements as physical PLCs, including strict sensitivity to jitter, packet loss, and communication interruptions.

Virtualized Safety PLCs and Timing Requirements

Virtualized safety PLCs execute safety-related logic in software and are designed to meet functional safety requirements up to SIL3, as defined by IEC 61508 and related standards.

In physical safety controllers, timing supervision is typically enforced using dedicated, redundant hardware clocks; to meet SIL3 requirements in virtual PLC environments, a supervised and fault-tolerant external time source is required.

This external time source ensures:

● Supervised time progression

● Detection of time drift, discontinuities, or loss of synchronization

● Fault handling consistent with safety integrity requirements

Vendor implementations address this requirement in different ways:

● CODESYS Virtual Safe Control SL uses a Time Service VM that distributes supervised time to vPLCs. The Time Service VM derives time from the ESXi host, which must be synchronized using Network Time Protocol (NTP). The Time Service VM may serve multiple vPLCs, with a second instance required for redundancy. Time Service VM must not run on the same host as the associated vPLC to meet safety requirements.

● Siemens SIMATIC S7-1500V with failsafe functions uses a per-host Virtual Time Service that distributes time to virtual controllers running on the same host. The Virtual Time Service requires dedicated, non-integrated network interfaces, implemented as separate PCIe NICs or externally connected IEEE 1588–capable network cards, with a built-in quartz oscillator and configured for PCI passthrough.

While implementation details differ, the architectural requirement is consistent: safety-capable vPLCs depend on an external, supervised, and resilient source of time. This CVD does not cover the configuration of vendor-specific time distribution applications. However, it is important to note that time distribution for safety applications in this design require:

● A dedicated virtual switch instance running on the host

● A dedicated VLAN to distribute time

For network implications and connectivity requirements between the SD-Access fabric and the data center, refer to the Data Center Interconnection section.

Black Channel Principle and SD-Access Fabrics

Safety communication over Ethernet follows the black channel principle (IEC 61508, IEC 61784-3), where the network is treated as an untrusted transport and safety measures are implemented end-to-end by the safety protocol and endpoints. Therefore, safety protocols such as PROFIsafe can operate over SD-Access fabrics provided the network meets the availability and communication performance required by the application.

Human-Machine Interfaces (HMI)

Virtualized HMIs (vHMIs) are supported as part of this architecture. HMI applications may run in the same data center environment as vPLCs or on separate compute resources, depending on operational requirements.

Operator access is typically provided through thin clients, industrial panels, or standard workstations on the factory floor. From an architectural perspective, vHMIs are latency-sensitive but not safety-critical and are treated as supervisory applications rather than control-plane components. While loss of HMI connectivity does not interrupt the control process, it removes operator visibility and interaction capabilities; therefore, resiliency requirements for HMIs must be evaluated based on operational risk and recovery expectations.

Engineering and Commissioning Applications

Engineering and commissioning tools are essential for development, maintenance, and lifecycle operations. These applications are typically deployed as:

● Centralized engineering workstations

● Virtual desktops or dedicated VMs in the data center

Examples include:

● CODESYS IDE

● Siemens TIA Portal

● Associated license servers and engineering services

These applications generate bursty, non-deterministic traffic and are operationally important, but do not participate in real-time control loops. Their requirements influence access, segmentation, and prioritization decisions, but they do not dictate the deterministic behavior of the network.

A Note on Motion Control

High-precision motion control and time-synchronized motion applications over SD-Access fall outside the scope of this CVD.

Validated Hardware and Software

The following tables summarize the hardware platforms and software versions used to validate the dual SD-Access fabric architecture for vPLC workloads, industrial protocols (e.g., PROFINET), and associated OT visibility and security components.

Table 3. Network Infrastructure (SD-Access and Industrial Network)

| Function |

Platform / Component |

Validated Version |

Notes |

| SD-Access fabric edge |

Catalyst 9300 Series and Catalyst 9500 Series |

IOS-XE 17.15 |

SD-Access fabric edge; PRP transport termination point |

| SD-Access fabric control & border |

Catalyst 9500 Series |

IOS-XE 17.15 |

SD-Access control-plane and border roles |

| Industrial Access |

Cisco Catalyst IE3400 Series |

IOS-XE 17.18.2 |

Policy extended node; supports PRP. |

| Network controller |

Cisco Catalyst Center |

3.1.6 |

Central provisioning, assurance, and lifecycle management |

| Policy & Segmentation |

Cisco Identity Services Engine (ISE) |

|

Central policy server for segmentation |

| OT Visibility |

Cisco Cyber Vision |

5.3.3 |

Embedded sensors and centralized OT visibility |

| Secure Remote Access |

Cisco Secure Equipment Access (SEA) |

Latest supported |

Deployment validated with SD-Access workflows |

Table 4. Virtualization layer

| Function |

Platform / Component |

Validated Version |

Notes |

| Virtualization Management |

VMware vCenter |

9.0 |

Centralized virtualization management |

| Virtual Switching |

VMware NSX (IVS) |

9.0 |

Virtual industrial switch for dual-fabric connectivity |

| Hypervisor |

VMware ESXi |

9.0 |

Hypervisor for vPLC and supporting workloads |

Table 5. Manufacturing Applications – Siemens Stack

| Component |

Role in Architecture |

Validated Version |

Notes |

| TIA Portal |

Engineering and configuration environment |

V20 Update 1 |

Used for PLC, safety, HMI, and device configuration |

| Industrial Edge Management (IEM) |

Centralized lifecycle and application management |

1.15.9 |

Management plane for Industrial Edge components |

| Industrial Edge Device Virtualization (IEDV) |

Virtualized runtime for industrial applications |

1.24.2-1 |

Hosts Siemens industrial workloads |

| Virtual PLC (S7-1500V) |

Execution of control logic in a virtualized environment |

V 2.1.0+09 |

vPLC workload |

| Safety PLC (S7-1500 Virtual Controller CPU 1517V(F) ) |

Execution of safety-related control logic |

V 2.2.0+03 |

SIL-capable safety functions |

| Virtual Time Service |

Supervised time distribution for safety applications |

V 1.0.0 |

Provides supervised time to failsafe vPLCs |

| Industrial Edge Hub |

Data aggregation and integration services |

NA |

Data handling and integration layer |

| WinCC Unified (vHMI) |

Virtualized HMI and operator interface |

V4.0.0 (WinCC Unified 6.0.0.20 - TIA V20 UP2) |

Operator visualization and control |

Table 6. Manufacturing Applications – CODESYS Stack

| Component |

Role in Architecture |

Validated Version |

Notes |

| CODESYS IDE |

Engineering and programming environment |

V3.5 SP21 Patch3 |

PLC and safety application development |

| CODESYS Virtual Control for Linux SL |

Execution of control logic in a virtualized environment |

4.18.0.0 |

vPLC workload |

| CODESYS Virtual Safe Control SL |

Execution of safety-related control logic |

4.18.0.0 |

Safety-capable control runtime |

| CODESYS Virtual Safe Timeprovider SL |

Supervised time distribution for safety-capable vPLCs |

4.18.0.0 |

Provides time services to Control Safe |

| License Management |

Licensing services for virtual controllers |

4.18.0.0 |

Centralized license handling |

Table 7. Test, Validation, and Operator Tools

| Tool / Component |

Role in Validation |

Version |

Notes |

| IXIA IxNetwork |

Traffic generation and scale testing |

N/A |

Used for congestion, failure, and QoS validation |

| EKS Box |

PROFINET scale and endurance testing |

N/A |

Industrial traffic stress and longevity tests |

| Thin Client running IGEL OS |

Operator and HMI access |

IGEL OS 11 |

Used for operator interaction and validation |

Dual SD-Access Fabric Networking Design

As explained in previous section, each SD-Access fabric operates as a complete, independent SD-Access domain, supporting the full set of functions required to deliver connectivity from the cell/area zone to the data center.

Each fabric independently includes:

● Industrial Ethernet switches providing connectivity to PLCs, I/O devices, HMIs, and cell/area zone equipment

● SD-Access edge nodes responsible for endpoint attachment and VXLAN encapsulation

● SD-Access control plane nodes providing endpoint-to-location mapping and fabric control functions

● SD-Access border nodes providing connectivity between the fabric and external networks, including the data center

These roles are implemented per fabric, as described in the Cisco SD-Access design guide, and are not shared between fabrics. Each fabric maintains its own control, forwarding, and policy enforcement domains. This design doesn’t cover design and best practices for SD-Access architecture. Refer Cisco Software-Defined Access Solution Design Guide for more information.

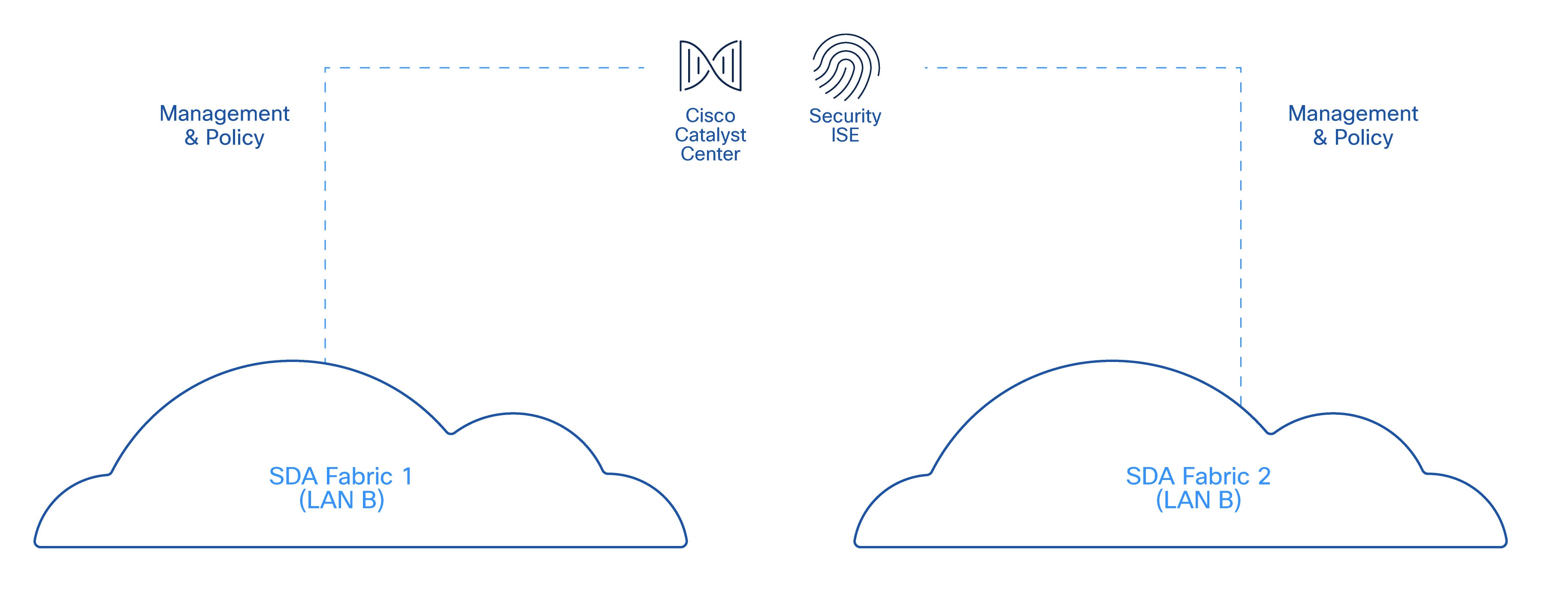

Management and Policy Plane Considerations

While the two fabrics are independent from a forwarding and control-plane perspective, they are operated under a shared management and policy framework.

● Catalyst Center is used to design, provision, and monitor both SD-Access fabrics

● A single Cisco ISE deployment provides centralized identity, authentication, and policy services

This shared management and policy plane simplifies operations and ensures consistent security posture across both fabrics. These shared components do not introduce shared forwarding dependencies. Loss of a management or policy service must not impact ongoing data-plane traffic in either fabric.

Figure 6 illustrates the shared management and policy plane across independent SD-Access fabrics.

vPLC architectures place critical manufacturing workloads in the data center, making data center connectivity a foundational dependency. The interconnection design must therefore provide high availability, predictable behavior, and support for maintenance activities without impacting production.

The data center interconnection is implemented using a fabric edge virtual switch stack to provide redundant physical connectivity and support in-service software upgrades. This allows maintenance activities to be performed without disrupting availability of virtualized workloads, including vPLCs and safety-related services.

This capability is essential in manufacturing environments where centralized compute resources must remain available during planned maintenance windows.

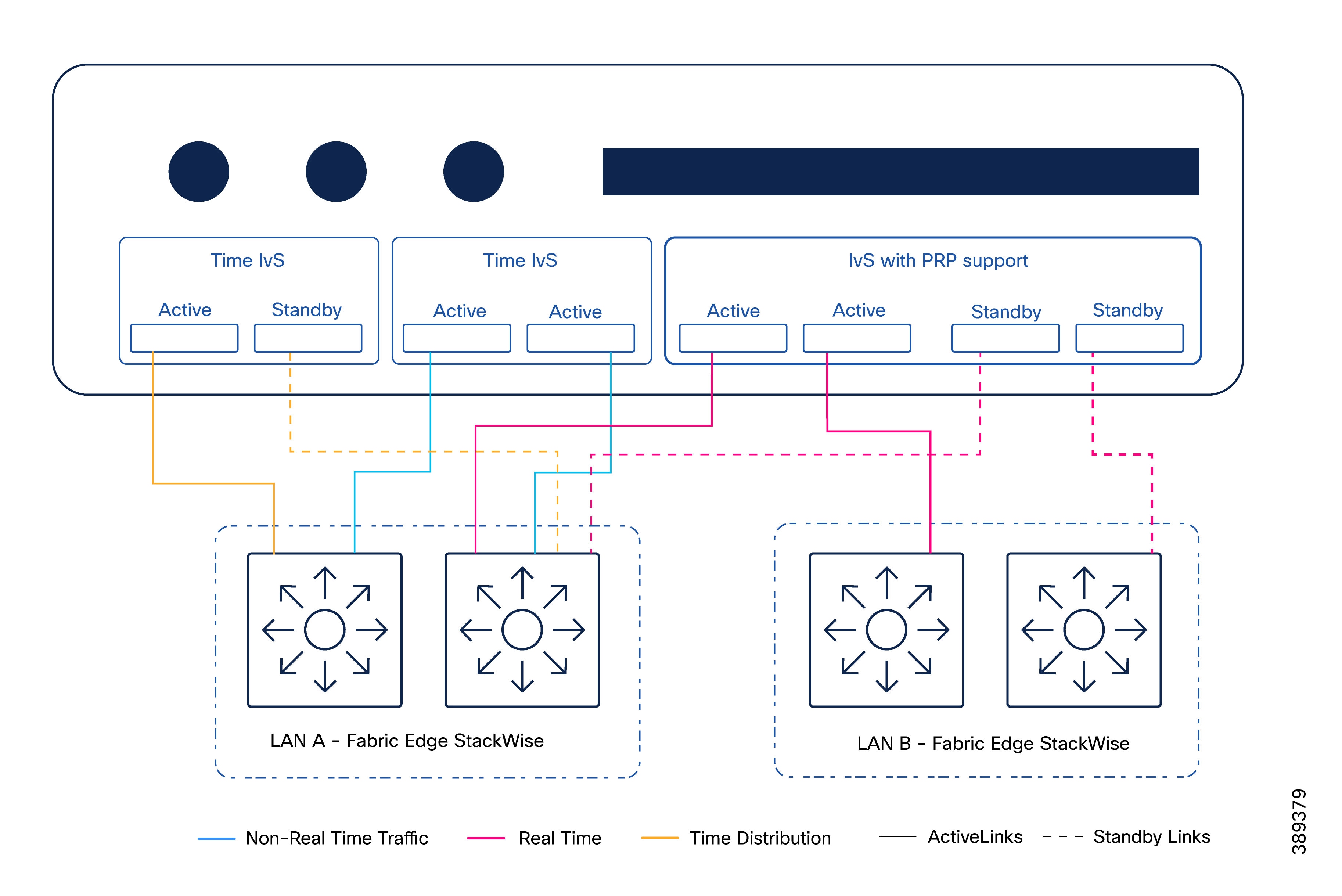

Figure 7 displays the connections between the server and the fabrics. The following section explains this connectivity.

Real-Time Traffic Connectivity to Dual Fabrics

The data center connects to both SD-Access fabrics to support real-time and safety-related traffic, depicted in pink in the diagram and terminating in the IvS.

The following list summarizes the connectivity characteristics:

● Each fabric provides one or more physical links to the data center.

● These links act as uplinks for the industrial virtual switch operating as a RedBox, providing connectivity to both fabrics.

● Interfaces are configured as Layer 2 trunks.

● Dual links to same fabric operate in an active/standby mode.

● Forwarding behavior is controlled by the virtual switching layer, not by the SD-Access fabrics.

This design allows real-time traffic to be transported over both fabrics while preserving complete fabric isolation and avoiding shared failure domains.

Non-Real-Time Traffic Handling

Non-real-time traffic is intentionally constrained to a single fabric (LAN A). This is depicted in blue in the connectivity diagram.

This includes virtualization platform management traffic, storage traffic, non-real-time application VLANs and overlays.

The following list summarizes the connectivity characteristics:

● Hosts connect only to LAN A for non-real-time services.

● Dual uplink per host is recommended for resiliency.

● Fabric edge interfaces toward the hosts are configured as Layer 2 trunks.

This separation reduces operational complexity and ensures that non-critical traffic does not interfere with real-time communication paths.

Time Distribution Connectivity for Safety PLCs

In some implementations (for example, CODESYS-based safety PLC deployments), time distribution for safety applications requires a dedicated network path. This is depicted in orange in the connectivity diagram.

The following list summarizes the connectivity characteristics:

● Time distribution traffic is switched only on LAN A fabric edge node.

● A dedicated VLAN is created on the fabric edge to transport this traffic.

● Flooding is not required, as time traffic remains local to the data center fabric edge.

● Given the nature of time-distribution packets, PTP must not be enabled on the fabric edge for this VLAN.

● When high utilization is expected across stack members, consider marking time distribution traffic with an appropriate Differentiated Services Code Point (DSCP) value to enable prioritization over less time-sensitive workloads (e.g., VSAN). This behavior is not validated in this CVD. Refer to Cisco guidance on QoS for Catalyst 9000 stack architectures. https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/collateral/switches/catalyst-9000/nb-06-cat-9k-stack-wp-cte-en.html#QualityofServicehttps://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/collateral/switches/catalyst-9000/nb-06-cat-9k-stack-wp-cte-en.html#QualityofService

This approach supports safety-related timing requirements while minimizing the impact on the SD-Access fabric.

Note: In architectures where time distribution is delivered over the network, PRP does not provide resiliency for timing. If the connectivity to the fabric edge node responsible for forwarding time traffic fails, time distribution between the time source and the safety PLC may be disrupted. This highlights an important design consideration when time distribution depends on network connectivity. Architectural enhancements should be explored to improve resiliency against network failures between the time distribution application and the fabric edge.

Cell/Area Zone Connectivity

At the cell/area zone level:

● An industrial Ethernet switch with PRP support (for example, IE3400) is deployed

● The switch is connected to both SD-Access fabrics simultaneously

● PRP is used to duplicate critical traffic toward both fabrics

This design ensures that loss of a single fabric, uplink, or intermediate node does not interrupt communication between the vPLC and field devices.

Summary of Architectural Characteristics

The architectural scope of the dual SD-Access fabric design can be summarized as follows:

● Each fabric is a complete SD-Access deployment with its own edge, control, and border nodes

● Management and policy services are centralized

● Both the data center and the cell/area zone are dual-connected using PRP-capable components

● Fabric independence is preserved end-to-end, from the factory floor to the data center

This design ensures that the dual fabric architecture delivers both the flexibility of SD-Access and the determinism required by industrial control systems.

PRP Operation Across Dual SD-Access Fabrics

In this architecture, PRP is used to protect application traffic that cannot tolerate packet loss or interruption, independent of network convergence behavior.

The dual SD-Access fabric design provides the two independent networks required by PRP:

● Fabric A (LAN A)

● Fabric B (LAN B)

Each PRP-protected frame is transmitted simultaneously across both fabrics. The receiving RedBox processes the first valid frame and discards the duplicate.

PRP Duplication Rules

PRP frame duplication occurs only when required, based on the knowledge of the PRP-capable device performing duplication, typically a RedBox. This decision is driven by the PRP node table maintained by that device. Entries for DANs and vDANs are populated through PRP supervisory frames exchanged between PRP-capable devices, while SANs are learned through normal data-plane traffic. Based on this information, duplication follows these rules:

● Frames destined to DANs are duplicated (for example, dual-attached I/O devices that natively support PRP).

● Frames destined to vDANs are duplicated (for example, endpoints presented as PRP-capable through a RedBox).

● Frames destined to unknown MAC addresses are duplicated during address learning or startup conditions.

● Frames destined to SANs are not duplicated (for example, endpoints connected to a single network only).

This behavior allows PRP to protect only traffic flows that require zero interruption, while avoiding unnecessary duplication of non-critical traffic.

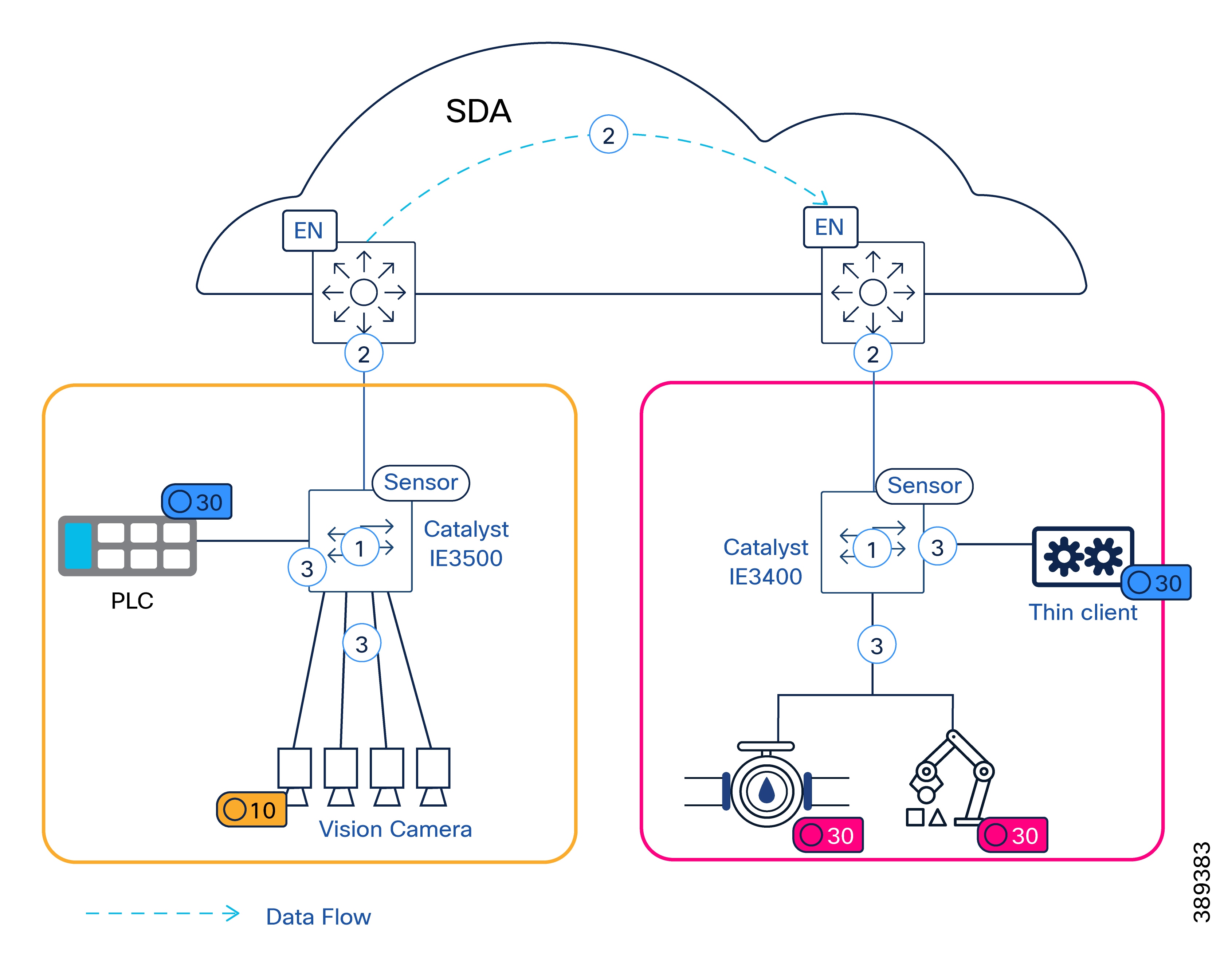

Manufacturing Example

Figure 8 maps the PRP duplication rules described in the previous section to the manufacturing example, highlighting how traffic is treated.

Consider a manufacturing cell where a vPLC with a PROFINET interface is connected behind a virtual RedBox, and distributed I/O devices are connected through a Catalyst IE3400 switch with PRP support. The PROFINET VLAN is instantiated in both SD-Access fabrics (LAN A and LAN B).

In this scenario, the virtual RedBox presents the vPLC as a vDAN, while the distributed I/O devices are also represented as vDANs, attached through the Catalyst IE3400 acting as a RedBox. PROFINET traffic sent by the I/O devices to the vPLC is duplicated by the Catalyst IE3400 based on its PRP node table, which identifies the vPLC as a DAN. As long as the VLAN is mapped to the same Layer 2 Virtual Network Identifier (L2VNI) in both fabrics and the PRP topology is correctly configured, control traffic is delivered without interruption even if one fabric experiences a failure. This selective duplication model ensures that only critical manufacturing traffic is protected, while other manufacturing and IT traffic continues to rely on standard SD-Access fabric resiliency mechanisms.

In contrast, traffic between the same I/O devices and a diagnostic or engineering workstation connected only to LAN A is not duplicated, as the destination is identified as a single attached node. As a result, the Catalyst IE3400 does not replicate this traffic.

Key Takeaway: PRP duplication is applied selectively based on the destination device and RedBox behavior, not simply by VLAN membership. While the VLAN must be present in both fabrics, frame replication occurs only when the destination is identified as PRP-capable.

PRP RedBox Placement in the Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

In this architecture, PRP functionality is implemented exclusively at the network access layer through RedBoxes. The SD-Access fabric itself remains transparent to PRP operation.

PRP RedBoxes are deployed at the following locations:

● Cell/Area Zone: Industrial Ethernet switches with PRP support (i.e. Catalyst IE3400) act as RedBoxes for single attached field devices (for example, I/O, and sensors).

● Data Center / Virtualization Layer: Virtual RedBoxes are used to represent virtualized workloads (such as vPLCs) as PRP-capable endpoints.

In this design, RedBoxes located in the cell/area zone are deployed as Policy Extended Nodes (PENs). As such, they operate strictly as Layer 2 devices and do not participate in SD-Access fabric control-plane or forwarding-plane functions.

PRP functionality is configured after PEN onboarding is completed using a Cisco Catalyst Center workflow. Refer to Catalyst IE3400 Commissioning and Replacement Procedures for more details.

Note: In this design, Policy Extended Nodes are provisioned and managed through only one of the single SD-Access fabric. To simplify operations, PEN management connectivity is provided exclusively via LAN A.

While the PEN maintains Layer 2 connectivity to critical OT VLANs in both fabrics, management and provisioning traffic is not duplicated. As a result, a link failure between the PEN and LAN A may render the device temporarily unreachable from a management perspective; however, critical manufacturing traffic continues to flow uninterrupted across both fabrics. Management access is restored once connectivity to LAN A is re-established.

Layer 2 and Layer 3 connectivity considerations for PENs are discussed in a later section of this document.

The following diagram illustrates the placement of PRP RedBoxes within the dual SD-Access fabric architecture and highlights how different endpoint types are represented from a PRP perspective.

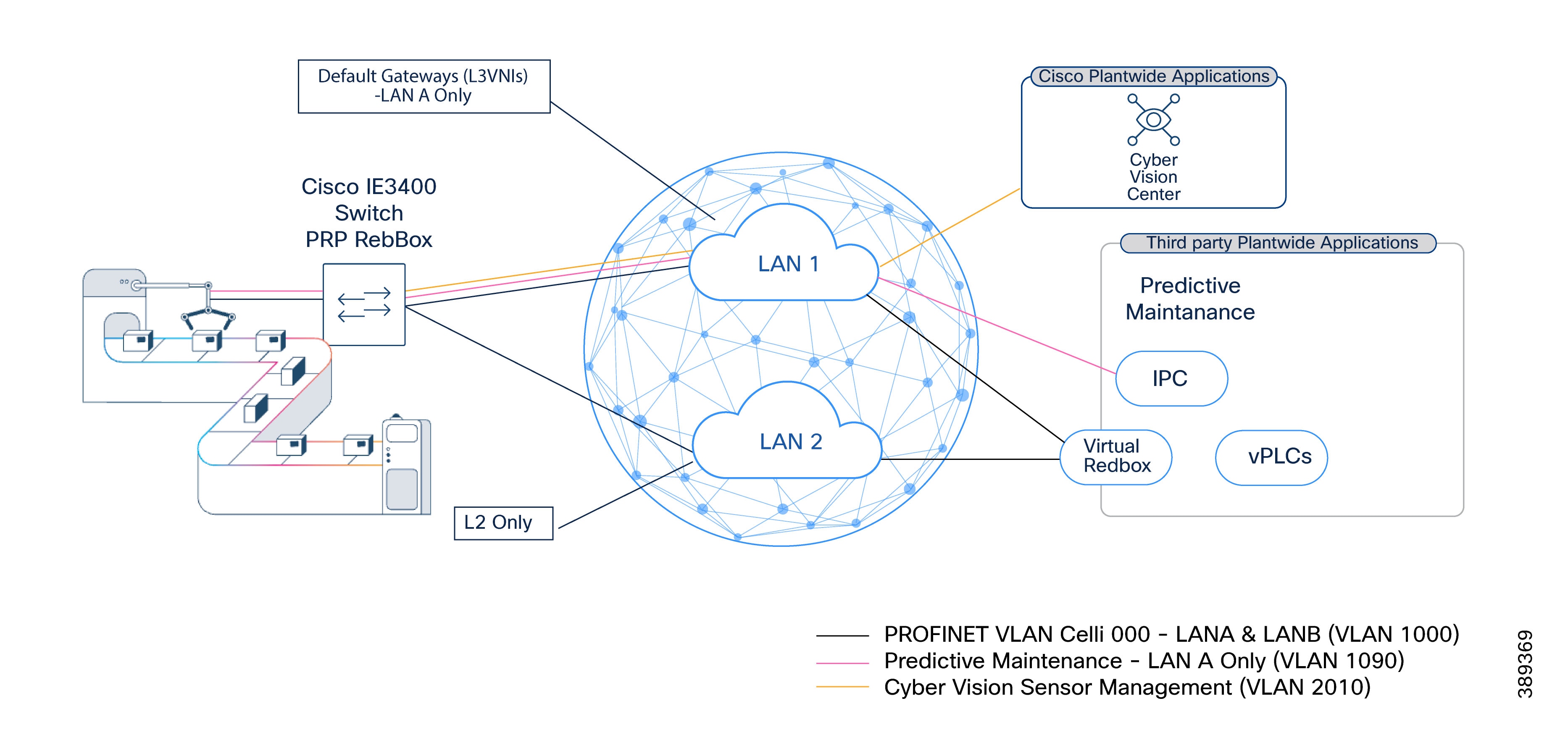

Layer 2 and Layer 3 Boundaries in Dual SD-Access Fabric

PRP in this architecture is intended to protect traffic that remains within the same VLAN. As a result, PRP-protected traffic must remain within a single broadcast domain.

In the dual SD-Access fabric architecture identical L2VNIs are created in both fabrics for traffic that requires PRP protection. For example, a PROFINET VLAN (VLAN 1000) is instantiated as the same L2VNI in Fabric A and Fabric B.This allows PRP duplication to occur across both fabrics while preserving logical adjacency.However, Layer 3 gateways represent a special case.

SD-Access default gateways are implemented on fabric edge nodes, which are SANs from a PRP perspective. As a result:

● A PRP-protected VLAN must have its default gateway in only one fabric

● The corresponding L3VNI is created only in that fabric

For clarity, this document refers to the fabric hosting the default gateway as LAN A.

LAN B carries duplicate Layer 2 traffic but does not host a gateway for that VLAN. Anycast gateways in this architecture are treated as single attached nodes (SANs) from a PRP perspective; deploying a gateway in both fabrics would introduce a PRP-incompatible multi-attached gateway and compromise correct PRP operation.

The following table serves as a reference for LAN A and LAN B configuration.

Table 8. LAN A and LAN B Virtual Network Configuration Reference

| LAN A (Primary Fabric Configuration) |

LAN B (Redundant Fabric Configuration) |

| Layer 3 virtual networks: Create VNs to define macro-segmentation (e.g., OT, IoT, and Management). |

Critical Applications Only (i.e. PROFINET): Create Layer 2 Virtual Networks specifically for critical applications. Non-critical traffic is not required on this fabric. |

| Standard Anycast Gateways: Create gateways for non-critical applications. |

VLAN ID Matching: Ensure VLAN IDs match exactly with those defined in LAN A for the corresponding critical applications. |

| Critical Application Gateways (i.e. PROFINET): Create gateways with Layer 2 flooding enabled to support PRP operation. |

Redundancy note: LAN B mirrors the critical L2 structures of LAN A to ensure seamless PRP (Parallel Redundancy Protocol) operation without duplicating non-essential traffic. |

| Extended Node Gateway: Create in the INFRA_VN to support Policy Extended Node (PEN) management. |

Example: Layer 2 and Layer 3 Boundaries for PRP and Non-PRP VLANs

Table 9 illustrates how VLANs are distributed across LAN A and LAN B in a dual SD-Access fabric architecture, using PROFINET and related manufacturing traffic as examples.

Table 9. Example: Layer 2 and Layer 3 Boundaries for PRP and Non-PRP VLANs

| VLAN ID |

Purpose |

LAN A (Fabric A) |

LAN B (Fabric B) |

VRF (LAN A) |

PRP Usage |

Design Notes |

| 1000–1003 |

PROFINET I/O (Critical Control) |

L2VNI + optional L3VNI (Gateway) |

L2VNI only |

OT VRF (if gateway present) |

Yes |

Identical L2VNIs in both fabrics. Default gateway, if required, exists only in LAN A. L2 flooding enabled in both fabrics for DCP discovery. |

| 1040 |

Infrastructure / Policy Extended Nodes |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

Underlay VRF |

No |

Infrastructure VLAN for PEN connectivity. Routed only in LAN A. Not extended to LAN B. |

| 1060 |

OT Application Management |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

OT VRF |

No |

Management traffic for OT applications. Routed only in LAN A, same VRF as PROFINET gateways. |

| 1080–1085 |

Data Center Management (vMotion, ESXi, vSAN) |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

DC Management VRF |

No |

Virtualization infrastructure traffic. Isolated in its own VRF and confined to LAN A. |

| 1090 |

MQTT / IoT Messaging |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

IoT VRF |

No |

Non-real-time IoT traffic. Routed only in LAN A. |

| 2000 |

Vision System Traffic |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

OT VRF |

No |

High-bandwidth, non-PRP traffic. Confined to LAN A. |

| 2010 |

Cyber Vision Sensors |

L2VNI + L3VNI (Gateway) |

Not present |

Management VRF |

No |

OT visibility traffic. Exists only in LAN A and isolated in a management VRF. |

Design Rules Reinforced by this example

· PRP-protected VLANs must be instantiated as identical L2VNIs in both LAN A and LAN B.

· A default gateway, if required, must exist in only one fabric, LAN A.

· VLANs that do not require PRP are confined to LAN A and use standard SD-Access L2/L3 behavior.

Figure 10 below illustrates PRP across two independent SD-Access fabrics. PRP VLANs are extended as L2VNIs in both LAN A and LAN B, while default gateways (L3VNIs), when required, exist only in LAN A. Non-PRP services are confined to LAN A to preserve fabric isolation and operational simplicity.

PRP Scale Considerations

PRP deployments must account for scale and operational behavior, particularly in large manufacturing environments and centralized data center architectures.

PRP Supervisory Frames and Default Behavior

In standard PRP operation, remote DANs and vDANs are learned by RedBoxes through PRP supervisory frames. These PRP supervisory frames are used to discover and maintain information about PRP-capable endpoints and are essential for correct duplication and de-duplication behavior.

By default:

● PRP supervisory frames are sent untagged (native VLAN)

● A RedBox learns any vDAN from any received supervision frame

● Learned vDANs are stored in a node table on the RedBox

This default behavior works well in small, flat Layer 2 deployments. However, it introduces challenges in SD-Access based fabrics and at scale.

Implications in SD-Access Based Fabrics

In SD-Access fabrics, untagged Ethernet frames are not forwarded through the fabric. As a result, default PRP supervisory frames would be dropped unless they are explicitly tagged.

To address this, industrial switches supporting PRP allow configuration of a single VLAN used for PRP supervisory traffic. This ensures that supervisory frames are properly encapsulated and forwarded through the SD-Access fabric.

PRP Scale Limitations

By default, a RedBox:

● Learns vDANs from all received supervisory frames and SAN from data traffic

● Stores learned endpoints in a node table with finite capacity

In large manufacturing deployments, especially those with many cells and zones and large numbers of vDANs, the number of learned vDANs may exceed the available table entries. This can result in:

● Inability to learn new PRP endpoints

● Unpredictable duplication behavior

For these environments, default PRP behavior may be unsuitable, for this reason PRP supervision VLAN aware mode was introduced as a feature on Catalyst IE3400 switches on IOS-XE 17.16.

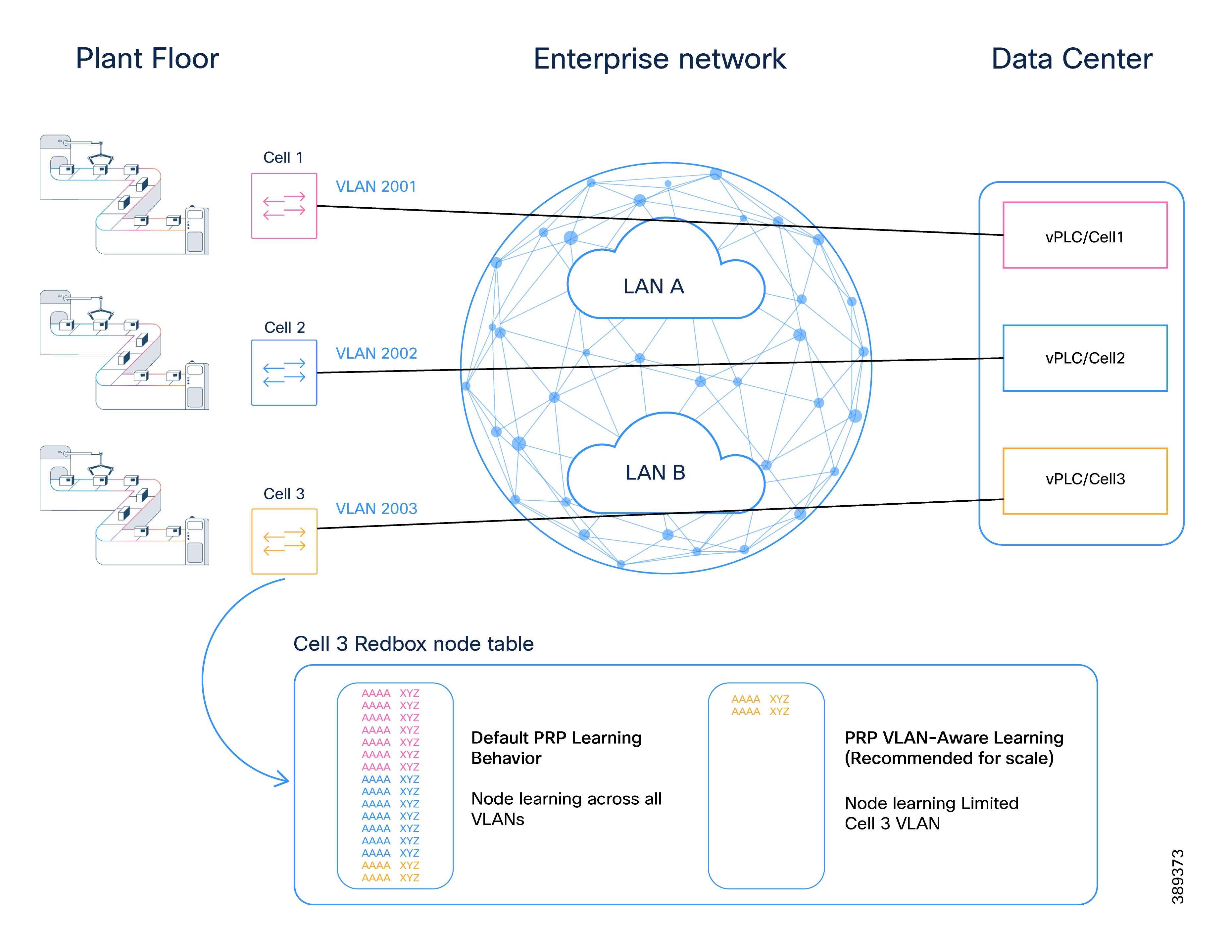

PRP supervision VLAN aware mode for Scalable Deployments

PRP supervision VLAN aware mode addresses these limitations by providing tighter control over PRP endpoint learning and duplication scope.

With PRP supervision VLAN aware mode:

● PRP supervisory frames are sent tagged on the data VLAN used by the application

● RedBoxes are explicitly configured to learn vDANs only from specific VLANs

● PRP learning and duplication are effectively scoped per VLAN

This allows the creation of logical “PRP domains”, where only endpoints participating in specified VLANs are learned on RedBoxes.

While “PRP domain” is not a formal IEC term, it is a useful conceptual model to describe VLAN-scoped PRP operation in large environments.

Example: PRP Scale on Centralized Data Center for vPLC

In factories using centralized data centers to host vPLCs or other critical applications, PRP supervision VLAN aware mode becomes particularly important.

Without PRP supervision VLAN aware mode:

● RedBoxes may learn vDANs from unrelated cells or production lines

● Node tables may be exhausted

● Operational isolation between applications is reduced

By scoping PRP learning to specific VLANs:

● PRP scale is controlled

● Application domains remain isolated

● Expansion becomes predictable and manageable

This approach aligns naturally with SD-Access segmentation models and large-scale manufacturing designs.

Operational Guidance for PRP supervision VLAN aware mode Configuration

For scalable and predictable PRP deployments:

● Use PRP supervision VLAN aware mode for scale

● Use VLAN tagging for PRP supervisory frames

● Ensure LAN A and LAN B are created consistently for all PRP-enabled VLANs

● Limit PRP learning to only the VLANs required by the applications in the cell/area zone

● Validate node table utilization during design and expansion phases

Configuration Workflow

Configuration of PRP supervision VLAN aware mode behavior can be automated using Catalyst Center.

Quality of Service Design

Manufacturing control traffic must receive consistent end-to-end prioritization across the industrial access layer, both SD-Access fabrics, and the data center. Any variation in classification, marking, or queue mapping can introduce delay or jitter that affects control applications.

The QoS design in this CVD ensures that:

● Control traffic is forwarded ahead of all other traffic.

● QoS behavior is consistent across Fabric A and Fabric B.

● VXLAN encapsulation does not remove priority treatment for Layer 2 industrial protocols.

● Priority treatment is preserved from the cell/area zone to the data center and back.

This section uses PROFINET as the industrial ethernet protocol. The same approach applies to other industrial real-time protocols.

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic Priority Model

Time-Critical Industrial Control traffic is placed in a strict priority queue on:

● Industrial access switches in the cell/area zone

● SD-Access fabric edge and border nodes

● Any intermediate routed transport carrying the VXLAN underlay

● Data center switching components carrying control traffic

Strict priority queuing ensures that time-critical industrial control traffic is always serviced ahead of other traffic classes. Under congestion, control traffic experiences minimal delay and jitter because lower-priority traffic cannot delay or block it, even when the network is heavily loaded.

The following sections explain how PROFINET RT traffic is identified within the network and prioritized at every hop.

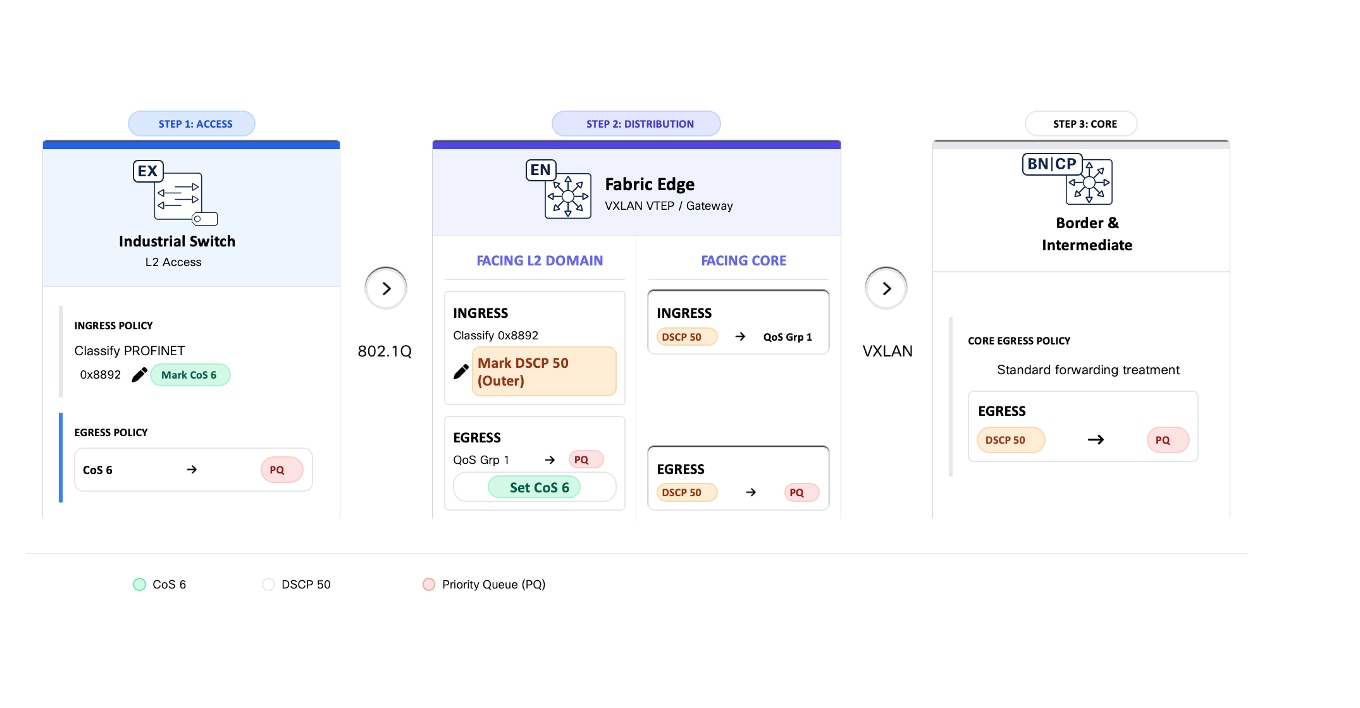

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic at the Industrial Access Layer

PROFINET RT traffic is identifiable by EtherType 0x8892 and is commonly marked with Class of Service (CoS) 6. To ensure consistent priority treatment, this design classifies control traffic at ingress rather than relying on endpoint markings.

On industrial access switches:

● Classify control traffic based on EtherType (0x8892).

● Set internal QoS values to map control traffic to the strict priority queue.

● Do not extend trust boundaries beyond the industrial access demarcation.

At this layer, queuing behavior is driven primarily by Layer 2 classification.

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic and VXLAN Encapsulation

When traffic enters the SD-Access fabric, it is encapsulated in VXLAN in order to be forwarded on the fabric overlay. For Layer 2 industrial protocols, VXLAN encapsulation introduces an important behavior:

Inside the SD-Access fabric, QoS decisions are made on the encapsulated (outer) headers, so the original Layer 2 markings must be mapped to an outer marking at ingress to preserve priority.

As a result, control traffic must be explicitly prioritized inside the SD-Access fabric using fields visible after encapsulation.

Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic Handling Inside the SD-Access Fabric

To preserve prioritization across the SD-Access fabric:

● Classify control traffic at the ingress fabric edge, for example by matching EtherType 0x8892 for PROFINET.

● Apply a dedicated DSCP value to the outer IP header of the VXLAN packet, using a non-commonly used value (DSCP 50) to avoid overlap with existing IT traffic classes.

● Ensure all SD-Access nodes map this DSCP value to the strict priority queue. This enables consistent treatment across routed fabric links and removes dependency on original Layer 2 markings.

Restoring Layer 2 Priority for Time-Critical Industrial Control Traffic at Fabric Egress

When traffic exits the SD-Access fabric toward the cell/area zone, VXLAN encapsulation is removed. At the egress fabric edge:

● Map the control traffic DSCP value to a QoS group at the fabric edge before the VXLAN header is removed. This allows the traffic to be correctly identified at the egress interface and remarked with the appropriate Layer 2 marking, for example, CoS 6.

● Ensure this traffic egresses via the strict priority queue.

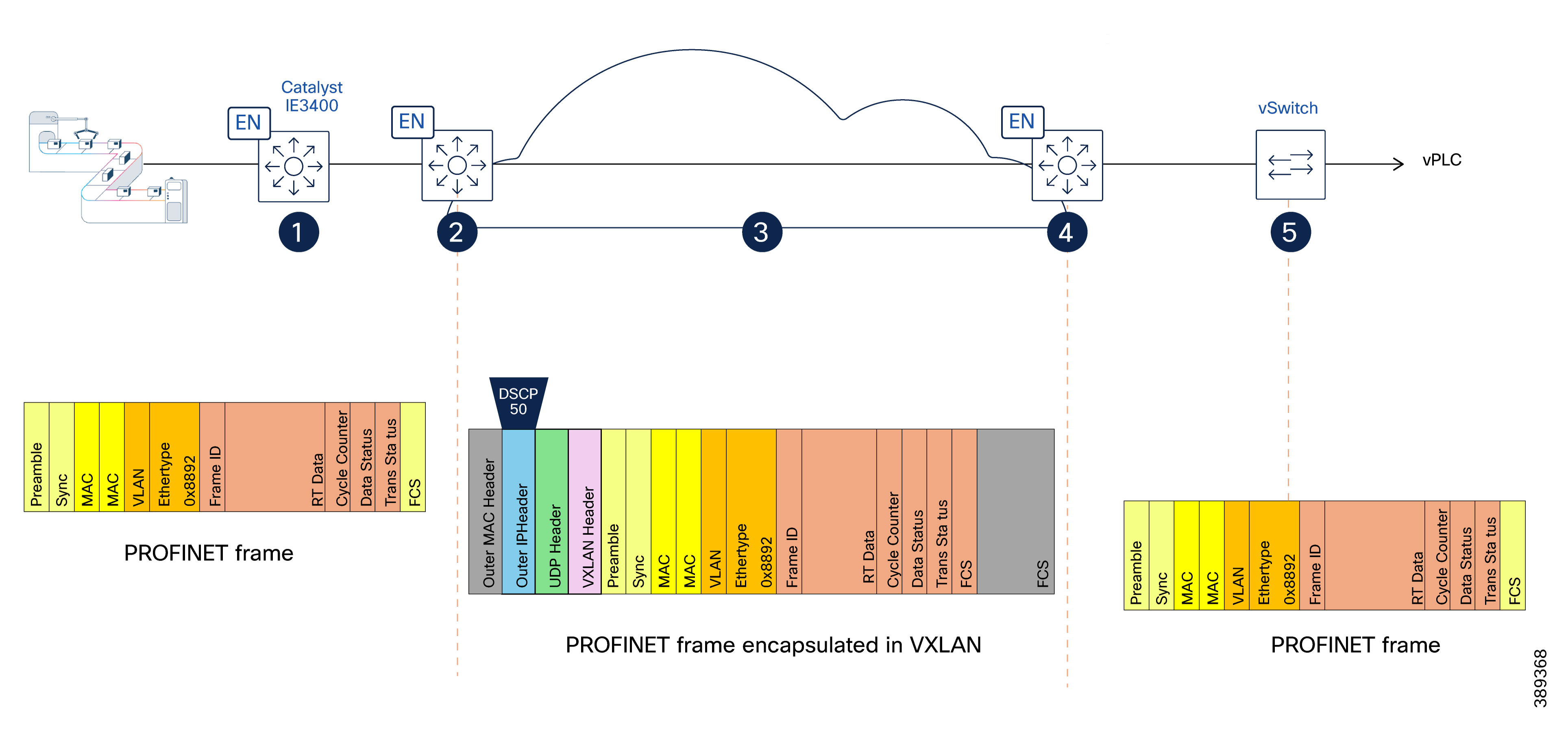

Summary: End-to-End PROFINET Frame Handling

Figure 12 illustrates how PROFINET real-time control traffic is classified, encapsulated, prioritized, and restored as it traverses from a vPLC in the data center, through an SD-Access fabric, and back into the industrial Layer 2 domain. It highlights how QoS markings are preserved across VXLAN encapsulation to ensure deterministic forwarding behavior for time-sensitive industrial protocols.

(1) Industrial Access – Native PROFINET Frame

PROFINET real-time control traffic is generated by field devices in the cell/area zone and forwarded by the industrial ethernet switch (Catalyst IE3400).

At this stage, traffic is a native Layer 2 PROFINET frame identified by EtherType 0x8892, with no IP header. The industrial access switch classifies the traffic and places it in the highest-priority queue to ensure preferential forwarding relative to other traffic classes.

(2) SD-Access Fabric Ingress – Classification and VXLAN Encapsulation

At the ingress SD-Access fabric edge, the PROFINET frame is classified based on EtherType (0x8892). The fabric edge encapsulates the Layer 2 frame into VXLAN for transport across the SD-Access fabric. During encapsulation, a dedicated DSCP value (for example, DSCP 50) is applied to the outer IP header to preserve priority treatment within the routed fabric.

(3) Transit Across the SD-Access Fabric – Routed Transport with Preserved Priority

The VXLAN-encapsulated packet traverses the SD-Access fabric using routed underlay links.

Forwarding and queuing decisions inside the fabric are based on the outer IP header. The DSCP marking ensures the packet uses the priority queue at every hop. The result is consistent priority treatment across all fabric nodes, independent of the original Layer 2 frame format.

(4) SD-Access Fabric Egress – Decapsulation and Priority Preservation

At the egress SD-Access fabric edge, VXLAN encapsulation is removed and the original PROFINET Layer 2 frame is restored.

The DSCP derived from the outer VXLAN/IP header is used to map the packet to a QoS group that it is used to put the frame at the appropriate egress queue and assign the Layer 2 priority (COS 6). This guarantees that priority treatment applied inside the fabric is preserved at the layer 2 domain.

(5) Virtual Switch to vPLC – Layer 2 Delivery

The PROFINET frame is delivered to the industrial virtual switch and forwarded to the virtualized PLC (vPLC).

Traffic remains Layer 2 end to end from the application perspective, with priority handling preserved through the network infrastructure.

Consistency Across Both Fabrics

QoS classification, marking, and queue mapping must be identical in Fabric A and Fabric B. Any mismatch (different DSCP values, queue maps, or template variations) can create asymmetric behavior and undermine bounded latency and jitter requirements.

Key QoS Design Principles for Dual SD-Access Fabric Architecture

● Inside the SD-Access fabric, control traffic priority is preserved via DSCP marking on the VXLAN outer header.

● Mapping between Layer 2 and Layer 3 markings must be enforced at fabric ingress and egress.

● Rate limiting and policing apply only to non-critical traffic classes; control traffic is not policed.

QoS Configuration Guidance

QoS policies for classification, marking, queue mapping, and scheduling are deployed using templates to ensure consistency across devices and both fabrics. Detailed configuration examples and validation steps are provided in Appendix - QoS Templates.

The following diagram illustrates the QoS policies applied across the switching infrastructure to preserve PROFINET RT priority end to end. The QoS policies provided align with this model and implement the behavior depicted here.

Layer 2 Flooding and Multicast Requirements

Certain industrial protocols rely on Layer 2 flooding or multicast behavior for device discovery and commissioning. For example, PROFINET uses the Discovery and Configuration Protocol (DCP) to perform device discovery and initial configuration, which requires Layer 2 broadcast communication.

By default, traffic in SD-Access overlays is not flooded, even when Layer 2 is extended. Flooding and multicast behavior must be explicitly enabled where required.

As a result:

● Layer 2 flooding must be enabled for any VLAN used by protocols that rely on broadcast or multicast communication.

● Flooding behavior must be applied consistently across both SD-Access fabrics for the relevant VLANs to ensure predictable operation.

In SD-Access configuration workflows:

● Layer 2 flooding is enabled by default for L2VNIs.

● For L3VNIs, flooding must be explicitly enabled when configuring the Anycast Gateway in Cisco Catalyst Center.

Layer 2 flooding in the overlay is supported by the underlay transport. When multicast-based replication is used, multicast routing must be enabled in the underlay to distribute broadcast, unknown unicast, and multicast (BUM) traffic across the fabric.

This underlay multicast configuration is typically enabled during LAN Automation in Catalyst Center, which provisions the required multicast routing and control-plane parameters as part of fabric bring-up. If multicast was not enabled during LAN Automation, it can later be provisioned using templates.

Failure to enable the appropriate underlay support for flooding may prevent device discovery and commissioning, even when overlay VLANs, VNIs, and policies are correctly defined.

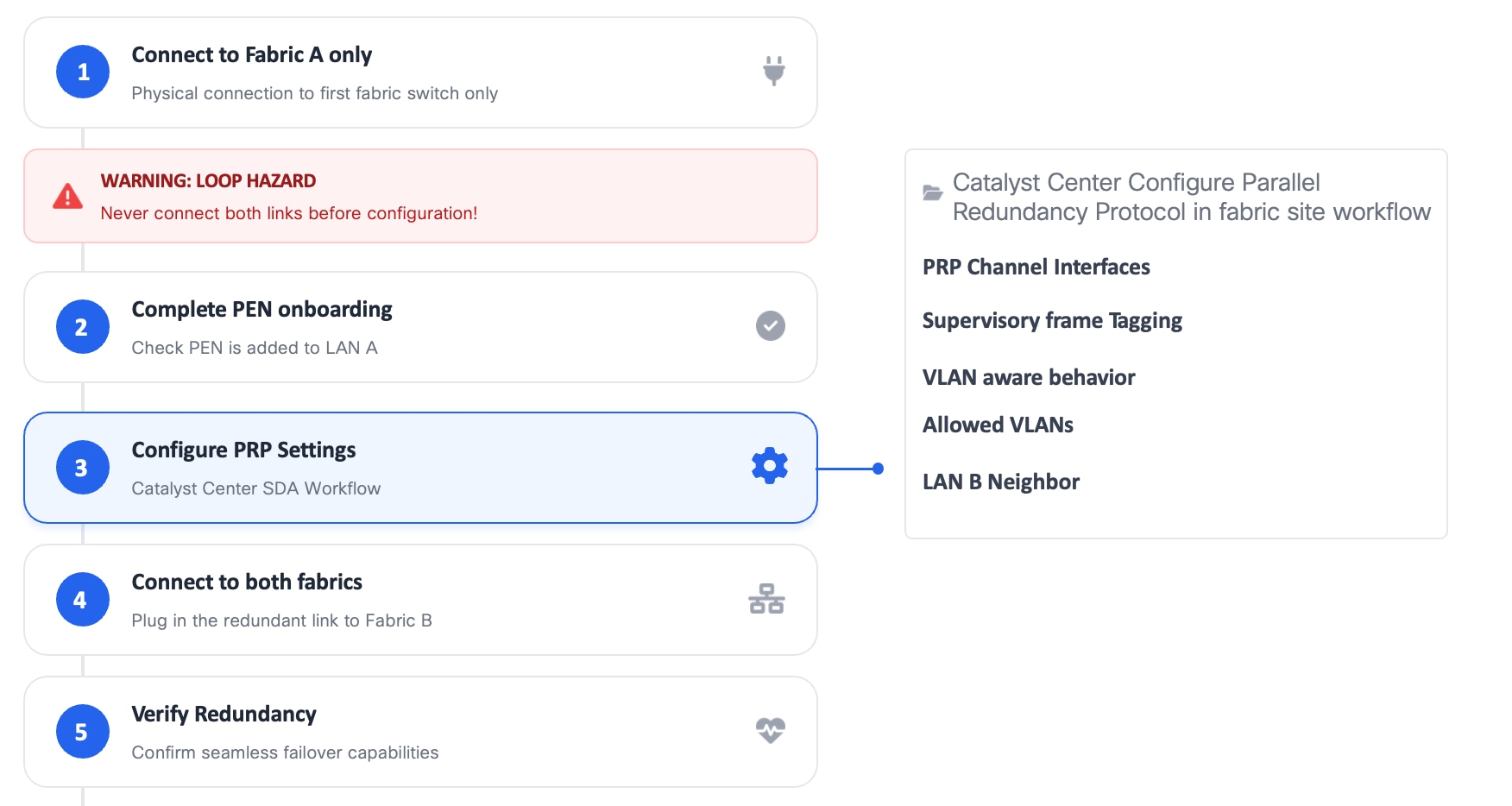

Catalyst IE3400 Commissioning and Replacement Procedures

PRP introduces specific operational requirements during commissioning and maintenance to prevent transient Layer 2 loops and unintended traffic duplication.

In particular:

● Nodes must not be dual-attached to both fabrics before PRP is fully configured.

● Improper sequencing during RedBox onboarding, replacement, or maintenance can temporarily create Layer 2 loops or flooding conditions.

● LAN A, which is used for management, must be the only active attachment until PRP configuration is completed.

To avoid unintended loops:

● RedBoxes must be commissioned using a controlled, step-by-step workflow.

● PRP configuration must be completed before connecting the LAN B interface.

● Replacement workflows must ensure that only the LAN A attachment is active until PRP configuration is verified.

● Onboarding warnings indicating potential loop hazards must be acknowledged and respected.

In SD-Access environments, these requirements are enforced through Cisco Catalyst Center configuration workflows, which guide the operator through:

● Initial onboarding of PEN to Fabric A (LAN A) only

● Completion of PRP configuration, including:

◦ Parallel Redundancy Protocol enablement

◦ PRP channel interfaces

◦ Supervisory frame tagging

◦ VLAN-aware behavior and allowed VLANs

◦ LAN B neighbor definition

● Controlled attachment of the redundant LAN B connection

● Final redundancy and failover verification

These procedures are critical in live manufacturing environments, where improper PRP commissioning or maintenance can affect production traffic beyond the individual RedBox being serviced. Figure below illustrates the commissioning steps. PRP RedBox commissioning workflow in Cisco Catalyst Center

Operational Considerations for PEN/RedBoxes

Policy Extended Nodes (PENs) enable non-fabric devices to participate in SD-Access policy enforcement. In manufacturing environments, however, their use introduces specific operational and lifecycle considerations that must be carefully evaluated.

At the time this CVD was written, the following constraints apply:

● PEN replacement (RMA) must be performed through Catalyst Center workflows.

● Standalone or locally driven replacement procedures are not supported for PEN devices.

● PEN onboarding, replacement, and recovery therefore depend on Catalyst Center workflows.

In manufacturing environments where rapid replacement and local intervention are common, these dependencies must be explicitly accounted for in operational planning.

Site-Based RBAC Implications

When Site-Based Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) is used:

● A PEN inherits the site assignment of its parent fabric edge.

● A PEN cannot be placed in a separate site or zone for more granular permission control.

As a result:

● Permissions applied to the parent fabric edge site implicitly apply to the PEN.

● Fine-grained delegation of access specifically for RedBox devices is not possible.

This behavior is particularly relevant when multiple operational teams, system integrators, or third-party vendors require differentiated access.

Placement of Industrial Ethernet Switches in SD-Access Based Manufacturing Networks

The following guidance applies to industrial switches that are connected to only one fabric. These Industrial Ethernet switches deployed on the manufacturing floor must not assume fabric roles such as fabric edge, Policy Extended Node, or Extended Node. Nevertheless, industrial Ethernet switches can still be managed by Catalyst Center and participate in micro-segmentation policies.

This guidance is driven by operational requirements, safety considerations, and predictable network behavior specific to manufacturing environments, as explained below.

Note that these switches must not forward time-critical industrial control traffic into the fabric, as traffic entering the fabric from a single attachment would not be protected by PRP and could compromise redundancy and availability.

Design Considerations and Operational Constraints

● Deterministic forwarding and fault behavior: industrial control and interlock traffic relies on predictable Layer 2 behavior. Assigning fabric roles to industrial switches introduces dependency on SD-Access forwarding. Even brief convergence events may introduce interruptions that are acceptable in IT networks but visible to time-sensitive manufacturing applications.

● Operational independence and recovery: manufacturing environments require local recovery and commissioning workflows. SD-Access role switches must be provisioned and replaced through Catalyst Center workflows and do not support SD-card–based or fully out-of-band configuration. This limits the ability of OT teams and system integrators to perform local intervention during commissioning or fault scenarios.

● Feature alignment with OT protocols: several OT-specific features are not supported or not validated when industrial switches operate under SD-Access workflows (for example, PROFINET, MRP, CIP-specific behaviors, and Layer 2 NAT). Keeping industrial switches outside the fabric preserves vendor-supported configurations and validated protocol behavior.

● Clear ownership boundaries: fabric devices inherit SD-Access permission models and site-based access control. Industrial switches acting as fabric devices cannot be delegated granular OT-only access, creating unnecessary coupling between IT-managed fabric operations and OT-owned production networks.