-

User Guide for Cisco Secure ACS for Windows 4.0

-

Preface

-

Overview

-

Deployment Considerations

-

Interface Configuration

-

Network Configuration

-

Shared Profile Components

-

User Group Management

-

User Management

-

System Configuration: Basic

-

System Configuration: Advanced

-

System Configuration: Authentication and Certificates

-

Logs and Reports

-

Administrators and Administrative Policy

-

User Databases

-

Posture Validation

-

Network Access Profiles

-

Unknown User Policy

-

User Group Mapping and Specification

-

Troubleshooting

-

TACACS+ Attribute-Value Pairs

-

RADIUS Attributes

-

CSUtil Database Utility

-

VPDN Processing

-

RDBMS Synchronization Import Definitions

-

Internal Architecture

-

Index

-

Table Of Contents

Basic Deployment Factors for ACS

Separation of Administrative and General Users

Network Latency and Reliability

Deployment Considerations

Deployment of Cisco Secure Access Control Server Release 4.0 for Windows, hereafter referred to as ACS, can be complex and iterative, depending on the specific implementation required. This chapter describes the deployment process and presents the factors that you should consider before deploying ACS.

The complexity of deploying ACS reflects the evolution of AAA servers in general, and the advanced capabilities, flexibility, and features of ACS in particular. AAA was conceived originally to provide a centralized point of control for user access via dial-up services. As user databases grew and the locations of AAA clients became more dispersed, more capability was required of the AAA server. Regional, and then global, requirements became common. Today, ACS is required to provide AAA services for dial-up access, dial-out access, wireless, VLAN access, firewalls, VPN concentrators, administrative controls, and more. The list of external databases that are supported has also continued to grow and the use of multiple databases, as well as multiple ACSs, has become more common. Regardless of the scope of your ACS deployment, the information in this chapter should prove valuable. If you have deployment questions that are not addressed in this guide, contact your Cisco technical representative for assistance.

This chapter contains the following topics:

•

Basic Deployment Factors for ACS

•

Suggested Deployment Sequence

For more documentation on deployment for NAC support, see the Go NAC site on Cisco.com. For minimum ACS system and client requirements refer to your installation guide or the Release Notes at http://www.cisco.com/univercd/cc/td/doc/product/access/acs_soft/csacs4nt/index.htm.

Basic Deployment Factors for ACS

Generally, the ease in deploying ACS is directly related to the complexity of the implementation that is planned, and the degree to which you have defined your policies and requirements. This section presents some basic factors that you should consider before you begin implementing ACS.

This section contains the following topics:

•

Network Latency and Reliability

Network Topology

How your enterprise network is configured is likely to be the most important factor in deploying ACS. While an exhaustive treatment of this topic is beyond the scope of this guide, this section details how the growth of network topology options has made ACS deployment decisions more complex.

When AAA was created, network access was restricted to devices that were directly connected to the LAN or remote devices that gained access via a modem. Today, enterprise networks can be complex and, because of tunneling technologies, can be widely geographically dispersed.

Dial-Up Topology

In the traditional model of dial-up access (a PPP connection), a user employing a modem or ISDN connection is granted access to an intranet via a network access server (NAS) functioning as a AAA client. Users may be able to connect via only a single AAA client as in a small business, or have the option of numerous geographically dispersed AAA clients.

In the small LAN environment, see Figure 2-1, network architects typically place a single ACS internal to the AAA client, which is protected from outside access by a firewall and the AAA client. In this environment, the user database is usually small, few devices require access to the ACS for AAA, and any database replication is limited to a secondary ACS as a backup.

Figure 2-1 Small Dial-up Network

In a larger dial-in environment, a single ACS with a backup may be suitable, too. The suitability of this configuration depends on network and server access latency. Figure 2-2 shows an example of a large dial-in arrangement. In this scenario the addition of a backup ACS is a recommended addition.

Figure 2-2 Large Dial-up Network

In a very large, geographically dispersed network (Figure 2-3), access servers might be located in different parts of a city, in different cities, or on different continents. If network latency is not an issue, a central ACS may work; but connection reliability over long distances may cause problems. In this case, local ACSs may be preferable to a central ACS. If the need for a globally coherent user database is most important, database replication or synchronization from a central ACS may be necessary. Authentication by using external databases, such as a Windows user database or the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), can further complicate the deployment of distributed, localized ACSs. While ACS uses encryption for all replication and database-synchronization traffic, additional security measures may be required to protect the network and user information that ACS sends across the WAN.

Figure 2-3 Geographically Dispersed Network

Wireless Network

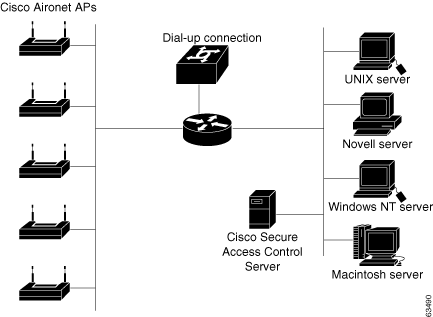

The wireless network access point is a relatively new client for AAA services. The wireless access point (AP), such as the Cisco Aironet series, provides a bridged connection for mobile end-user clients into the LAN. Authentication is absolutely necessary due to the ease of access to the AP. Encryption is also necessary because of the ease of eavesdropping on communications. As such, security plays an even bigger role than in the dial-up scenario and is discussed in more detail later in this section.

Scaling can be a serious issue in the wireless network. The mobility factor of the wireless LAN (WLAN) requires considerations similar to those given to the dial-up network. Unlike the wired LAN, however, the WLAN can be more readily expanded. Though WLAN technology does have physical limits as to the number of users that can be connected via an AP, the number of APs can grow quickly. As with the dial-up network, you can structure your WLAN to allow full access for all users, or to provide restricted access to different subnets between sites, buildings, floors, or rooms. This raises a unique issue with the WLAN: the ability of a user to roam between APs.

In the simple WLAN, there may be a single AP installed (Figure 2-4). Because there is only one AP, the primary issue is security. In this environment, there is generally a small user base and few network devices to worry about. Providing AAA services to the other devices on the network does not cause any significant additional load on the ACS.

Figure 2-4 Simple WLAN

In the LAN where a number of APs are deployed, as in a large building or a campus environment, your decisions on how to deploy ACS become more complex. Figure 2-5 shows all APs on the same LAN; however, they may be distributed throughout the LAN, and connected via routers, switches, and so on. In the larger, geographical distribution of WLANs, deployment of ACS is similar to that of large regional distribution of dial-up LANs (Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-5 Campus WLAN

This is particularly true when the regional topology is the campus WLAN. This model starts to change when you deploy WLANs in many small sites that more resemble the simple WLAN shown in Figure 2-4. This model may apply to a chain of small stores that are distributed throughout a city or state, nationally, or globally (Figure 2-6).

Figure 2-6 Large Deployment of Small Sites

For the model in Figure 2-6, the location of ACS depends on whether all users need access on any AP, or require only regional or local network access. Along with database type, these factors control whether local or regional ACSs are required, and how database continuity is maintained. In this very large deployment model, security becomes a more complicated issue, too.

Remote Access using VPN

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) use advanced encryption and tunneling to permit organizations to establish secure, end-to-end, private network connections over third-party networks, such as the Internet or extranets (Figure 2-7). The benefits of a VPN include the following:

•

Cost Savings—By leveraging third-party networks with VPN, organizations no longer have to use expensive leased or frame relay lines, and can connect remote users to their corporate networks via a local Internet service provider (ISP); instead of using expensive toll-free or long-distance calls to resource-consuming modem banks.

•

Security—VPNs provide the highest level of security by using advanced encryption and authentication protocols that protect data from unauthorized access.

•

Scalability—VPNs allow corporations to use remote-access infrastructure within ISPs; therefore, corporations can add a large amount of capacity without adding significant infrastructure.

•

Compatibility with Broadband Technology—VPNs allow mobile workers and telecommuters to take advantage of high-speed, broadband connectivity, such as DSL and cable, when gaining access to their corporate networks thereby, providing workers significant flexibility and efficiency.

Figure 2-7 Simple VPN Configuration

The two types of VPN access into a network are:

•

Site-to-Site VPNs—Extend the classic WAN by providing large-scale encryption between multiple fixed sites, such as remote offices and central offices, over a public network, such as the Internet.

•

Remote-Access VPNs—Permit secure, encrypted connections between mobile or remote users and their corporate networks via a third-party network, such as an ISP, via VPN client software.

Generally speaking, site-to-site VPNs can be viewed as a typical WAN connection and are not usually configured to use AAA to secure the initial connection and are likely to use the device-oriented IPSec tunneling protocol. Remote-access VPNs, however, are similar to classic remote connection technology (modem/ISDN) and lend themselves to using the AAA model very effectively (Figure 2-8).

Figure 2-8 Enterprise VPN Solution

For more information about implementing VPN solutions, see the reference guide A Primer for Implementing a Cisco Virtual Private Network.

Remote Access Policy

Remote access is a broad concept. In general, it defines how the user can connect to the LAN, or from the LAN to outside resources (that is, the Internet). There are several ways connectivity is possible, dial-in, ISDN, wireless bridges, and secure Internet connections. Each method incurs its own advantages and disadvantages, and provides a unique challenge to providing AAA services. This closely ties remote access policies to the enterprise network topology. In addition to the method of access, other decisions can also affect how ACS is deployed; these include specific network routing (access lists), time-of-day access, individual restrictions on AAA client access, access control lists (ACLs), and so on.

Remote access policies can be implemented for employees who telecommute, or mobile users who dial in over ISDN or a public switched telephone network (PSTN). Such policies are enforced at the corporate campus with ACS and the AAA client. Inside the enterprise network, remote access policies can control wireless access by individual employees.

ACS remote access policies provides control by using central authentication and authorization of remote users. The Cisco user database maintains all user IDs, passwords, and privileges. ACS access policies can be downloaded in the form of ACLs to network access servers such as the Cisco AS5300 Network Access Server, or by allowing access during specific periods, or on specific access servers.

Remote access policies are part of overall corporate security policy.

Security Policy

We recommend that every organization that maintains a network develop a security policy for the organization. The sophistication, nature, and scope of your security policy directly affect how you deploy ACS.

For more information about developing and maintaining a comprehensive security policy, refer to the following documents:

•

Network Security Policy: Best Practices White Paper

•

Cisco IOS Security Configuration Guide

Administrative Access Policy

Managing a network is a matter of scale. Providing a policy for administrative access to network devices depends directly on the size of the network and the number of administrators required to maintain the network. Local authentication on a network device can be performed, but it is not scalable. The use of network management tools can help in large networks; but if local authentication is used on each network device, the policy usually entails a single login on the network device. This does not promote adequate network device security. Using ACS allows a centralized administrator database, and administrators can be added or deleted at one location. TACACS+ is the recommended AAA protocol for controlling AAA client administrative access because of its ability to provide per-command control (command authorization) of AAA client administrator access to the device. RADIUS is not well suited for this purpose because of the one-time transfer of authorization information at the time of initial authentication.

The type of access is also an important consideration. In the case of different administrative access levels to the AAA clients, or if a subset of administrators is to be limited to certain systems, ACS can be used with command authorization per network device to restrict network administrators as necessary. Using local authentication restricts the administrative access policy to no login on a device or using privilege levels to control access. Controlling access by means of privilege levels is cumbersome and not very scalable. This requires that the privilege levels of specific commands are altered on the AAA client device and specific privilege levels are defined for the user login. You can easily create more problems by editing command privilege levels. Using command authorization on ACS does not require that you alter the privilege level of controlled commands. The AAA client sends the command to ACS to be parsed and ACS determines whether the administrator has permission to use the command. The use of AAA allows authentication on any AAA client to any user on ACS and limits access to these devices on a per-AAA-client basis.

A small network with a small number of network devices may require only one or two individuals to administer it. Local authentication on the device is usually sufficient. If you require more granular control than what authentication can provide, some means of authorization is necessary. As discussed earlier, controlling access by using privilege levels can be cumbersome. ACS reduces this problem.

In large enterprise networks, with many devices to administer, the use of ACS practically becomes a necessity. Because administration of many devices requires a larger number of network administrators, with varying levels of access, the use of local control is simply not a viable way of keeping track of network device configuration changes that are required when changing administrators or devices. The use of network management tools, such as CiscoWorks, helps to ease this burden; but maintaining security is still an issue. Because ACS can comfortably handle up to 300,000 users, the number of network administrators that ACS supports is rarely an issue. If a large remote-access population is using RADIUS for AAA support, the corporate IT team should consider separate TACACS+ authentication by using ACS for the administrative team. Separate TACACS+ authentication would isolate the general user population from the administrative team and reduce the likelihood of inadvertent access to network devices. If this is not a suitable solution, using TACACS+ for administrative (shell/exec) logins, and RADIUS for remote network access, provides sufficient security for the network devices.

Separation of Administrative and General Users

You should prevent the general network user from accessing network devices. Even though the general user may not intend to gain unauthorized access, inadvertent access could accidentally disrupt network access. AAA and ACS provide the means to separate the general user from the administrative user.

The easiest, and recommended, method to perform such separation is to use RADIUS for the general remote-access user and TACACS+ for the administrative user. One issue is that an administrator may also require remote network access, like the general user. If you use AC,S this issue poses no problem. The administrator can have RADIUS and TACACS+ configurations in ACS. Using authorization, RADIUS users can set PPP (or other network access protocols) as the permitted protocol. Under TACACS+, only the administrator would be configured to allow shell (exec) access.

For example, if the administrator is dialing in to the network as a general user, a AAA client would use RADIUS as the authenticating and authorizing protocol, and the PPP protocol would be authorized. In turn, if the same administrator remotely connects to a AAA client to make configuration changes, the AAA client would use the TACACS+ protocol for authentication and authorization. Because this administrator is configured on ACS with permission for shell under TACACS+, the administrator would be authorized to log in to that device. This does require that the AAA client have two separate configurations on ACS, one for RADIUS and one for TACACS+. An example of a AAA client configuration under IOS that effectively separates PPP and shell logins is:

aaa new-model tacacs-server host ip-address tacacs-server key secret-key radius-server host ip-address radius-server key secret-key aaa authentication ppp default group radius aaa authentication login default group tacacs+ local aaa authentication login console none aaa authorization network default group radius aaa authorization exec default group tacacs+ none aaa authorization command 15 default group tacacs+ none username user password password line con 0 login authentication consoleConversely, if a general user attempts to use his or her remote access to log in to a network device, ACS checks and approves the username and password; but the authorization process would fail because that user would not have credentials that allow shell or exec access to the device.

Database

Aside from topological considerations, the user database is one of the most influential factors in deployment decisions for ACS. The size of the user base, distribution of users throughout the network, access requirements, and type of user database are all factors when deciding how ACS is deployed.

Number of Users

ACS is designed for the enterprise environment, and can handle 300,000 users. This capacity is usually more than adequate for a corporation. In an environment that exceeds these numbers, the user base would typically be geographically dispersed, which requires the use of more than one ACS configuration. A WAN failure could render a local network inaccessible because of the loss of the authentication server. In addition to this issue, reducing the number of users that a single ACS handles improves performance by lowering the number of logins occurring at any given time and reducing the load on the database.

Type of Database

ACS supports several database options, including the ACS internal database or using remote authentication with any of the external databases supported. For more information about database options, types, and features, see Table 1-2 specifies non-EAP authentication protocol support., Chapter 13 "User Databases," or Chapter 17 "User Group Mapping and Specification." Each database option has its own advantages and limitations in scalability and performance.

Network Latency and Reliability

Network latency and reliability are also important factors in how you deploy ACS. Delays in authentication can result in timeouts at the end-user client or the AAA client.

The general rule for large, extended networks, such as those in a globally dispersed corporation, is to have at least one ACS deployed in each region. This configuration may not be adequate without a reliable, high-speed connection between sites. Many corporations use secure VPN connections between sites so that the Internet provides the link. This option saves time and money; but it does not provide the speed and reliability of a dedicated frame relay or T1 link. If a reliable authentication service is critical to business functionality, such as retail outlets with cash registers that are linked by a WLAN, the loss of WAN connection to a remote ACS could be catastrophic.

The same issue can be applied to an external database used by ACS. The database should be deployed close enough to ACS to ensure reliable and timely access. Using a local ACS with a remote database can result in the same problems as using a remote ACS. Another possible problem in this scenario is that a user may experience timeout problems. The AAA client would be able to contact ACS, but ACS would wait for a reply that might be delayed or never arrive from the external user database. If the ACS were remote, the AAA client would time out and try an alternate method to authenticate the user; but in the latter case, it is likely the end-user client would time out first.

Suggested Deployment Sequence

While no single process for all ACS deployments is recommended, you should consider following the sequence, keyed to the high-level functions that are represented in the navigation toolbar. Also remember that many of these deployment activities are iterative in nature; you may find that you repeatedly return to such tasks as interface configuration as your deployment proceeds.

The recommended sequence of configuration tasks is:

•

Configure Administrators—You should configure at least one administrator at the outset of deployment; otherwise, no remote administrative access is available, and all configuration activity must be done from the server. You should also have a detailed plan for establishing and maintaining an administrative policy.

For more information about setting up administrators, see Chapter 1 "Overview." For more detailed information on administrative controls, see Chapter 12 "Administrators and Administrative Policy."

•

Configure the ACS Web Interface—You can configure the ACS web interface to show only those features and controls that you intend to use. This option makes using ACS easier than it would be if you had to contend with multiple parts of the web interface that you do not plan to use. However, you should first ensure that you have correctly configured the features and controls that you require, in the Interface Configuration section. For guidance on configuring the web interface, see Interface Design Concepts.

For information about configuring particular aspects of the web interface, see the following sections:

–

User Data Configuration Options

–

Protocol Configuration Options for TACACS+

–

Protocol Configuration Options for RADIUS

•

Configure System—The System Configuration section contains more than a dozen functions to be considered, from setting the format for the display of dates and password validation to configuring settings for database replication and RDBMS synchronization. These functions are detailed in Chapter 8 "System Configuration: Basic" and Chapter 9 "System Configuration: Advanced." Also note that during initial system configuration you must set up the logs and reports to be generated by ACS; for more information, see Chapter 1 "Overview."

•

Configure Network—You control distributed and proxied AAA functions in the Network Configuration section of the web interface. From here, you establish the identity, location, and grouping of AAA clients and servers, and determine what authentication protocols each is to use. For more information, see Chapter 4 "Network Configuration."

•

Configure External User Database—During this phase of deployment you must decide whether and how you intend to implement an external database to establish and maintain user authentication accounts. Typically, this decision is made according to your existing network administration mechanisms. For information about the types of databases ACS supports and instructions for establishing them, see Chapter 13 "User Databases."

Along with the decision to implement an external user database (or databases), you should have detailed plans that specify your requirements for ACS database replication, backup, and synchronization. These aspects of configuring ACS internal database management are detailed in Chapter 8 "System Configuration: Basic."

•

Configure Shared Profile Components—With most aspects of network configuration already established and before configuring user groups, you should configure your Shared Profile Components. When you set up and name the network access restrictions and command authorization sets that you intend to employ, you lay out an efficient basis for specifying user group and single-user access privileges. For more information about Shared Profile Components, see Chapter 5 "Shared Profile Components."

•

Network Access Profiles—Provides a way to set up network access classifications according to values that you set along with rules or policies for authentication, posture validation, and authorization. For information on network access profiles, see Chapter 15 "Network Access Profiles."

•

Configure Groups—Having previously configured any external user databases that you intend to employ, and before configuring your user groups, you should decide how to implement two other ACS features that are related to external user databases: unknown user processing and database group mapping. For more information, see About Unknown User Authentication and Chapter 17 "User Group Mapping and Specification." Then, you can configure your user groups with a complete plan of how ACS is to implement authorization and authentication. For more information, see Chapter 6 "User Group Management".

•

Configure Users—With groups established, you can establish user accounts. Remember that a particular user can belong to only one user group, and that settings made at the user level override settings made at the group level. For more information, see Chapter 7 "User Management."

•

Configure Reports—Using the Reports and Activities section of the ACS web interface, you can specify the nature and scope of logging that ACS performs. For a summary of the logging reports information, see Chapter 1 "Overview." For information on how to set up logging, see Chapter 11 "Logs and Reports."

Feedback

Feedback